‘Pope Francis’ is a disturbing film, not solely for its exaltation of Francis and his politics but more so for having been planned from the beginning of his ascent to office.

By Maureen Mullarkey

May 30, 2018

Jorge Bergoglio found his Leni Riefenstahl in Wim Wenders. I went to see Wenders’ “Pope Francis: A Man of His Word” expecting hagiography. What I watched came closer to pornography. It was the pornography of blatant propaganda, that notorious key to “the heart of the broad masses.” Lust for dominance is airbrushed into a semblance of piety; avarice for celebrity is lighted and staged to look like humility.

Contrary to the court press, Damon Linker recently ascribed “psychological acuity and Machiavellian cunning” to Pope Francis. And he is correct. But Linker’s interest lies in the Catholic Church’s eventual alignment with contemporary mores, especially legitimization of homosexuality. Yet there remains a larger, more compelling issue: the sacralization of politics via the person of the pope himself. Francis is not reforming the church but denaturing it, reducing it to a social tool.

Commissioned by the Vatican, the film ups the ante on papalolotry. Its deluge of glorifying images stimulates devotion to Bergoglio himself, papa to all the world. A quasi-erotic glow infuses the whole. It is the eros of surrender to a liberator, a defender against ideological bogeys: “the globalization of indifference”; “money drenched in blood”; “fear of foreigners.” The old creed proclaimed Christ risen. The new Bergoglian one, emblazoned on St. Peter’s dome during the 2016 light show repeated here, proclaims: “Planet Earth first.”

The West “must become a little bit poorer” and repent for despoiling Sister Planet. Francis rails against “the culture of waste” of a rapacious West that clings to the wealth belonging to all. As if he were stating something new, Francis declares, “Poverty is an outrage.” Even “a hard-boiled American” can be moved by the sight of how much “we have plundered Mother Earth.” Follow Francis back to the original, unspoiled “harmony of creation.”

A Misty Drift Back to Saint Francis

Wenders’ cinematic borrowings are as unsubtle as Francis’ leftism. “Triumph of the Will” opened with a misty drift back in time to the ruins of ancient Greece. Just so, Pope Francis opens with a misty drift back to the Umbrian hills of St. Francis of Assisi. Wenders’ voice accompanies the glide with a gloss on the mystery of time.

Riefenstahl’s Grecian statues metamorphosed into living dancers. Wender’s view of Giotto’s fresco of St. Francis in the Scrovegni Chapel morphs into black-and-white footage—silent film-style—of a live actor playing a soulful saint. A nostalgic camera device, it breaks in to the modern color footage periodically to emphasize Bergoglio as the avatar of his thirteenth-century namesake.

The rest is predictable, surprising only in its derivative cinematography. Echoing ecstatic scenes of Nuremberg rallies, the roar of crowds is as much a subject as Francis himself. Wenders employs fast-moving follow shots: the camera runs behind Francis’ head as he stands in a vehicle moving swiftly past adoring throngs. The sound track is stirring; the mass jubilation rousing.

We learn close to nothing about the man himself beyond the already established image. Of life before the papacy, there is only a single archival clip of him stirring a crowd in Buenos Aires in the 1990s. He speaks more in the manner of a Peronist labor leader or politician on the stump than an archbishop.

At every junket, from the Philippines to refugee camps and the Middle East, the camera moves in as he works the crowd, lingering on tearful and rapturous faces. It keeps vigil while an old woman holds his hand to her mouth too long. It stays close while men kiss and caress him, some chanting “Nobel! Nobel!” It seizes exuberant banners and placards: “Grazie, Papa!” Francis revels in the adulation.

A Series Of Staged Images

Who remembers the staged photograph of President Clinton, solemn and solitary, walking on Omaha Beach? Or President Obama having himself photographed, solemn and solitary, on a beach along the gulf after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill? Wenders repeats the gambit multiple times throughout the film.

Here is Francis, solemn and solitary, gazing at the River Jordan, standing at the Western Wall, or contemplating a ruined street. Filmed from behind, this particular shot conjures up Gary Cooper walking alone into the center of Hadleyville. It is High Noon wherever Francis sets foot.

Apocalyptic footage of Hiroshima appears. Bergoglio was a toddler at the time. But he presents himself as the speaker in Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself”: “I am the man, I suffered, I was there.” The pose does nothing to illumine the complexities of the Hiroshima bombing or the tragic necessities of defensive war—something earlier popes understood in anguish.

The camera rolls back to let distance dramatize the pope’s lonely exit from his tour of Auschwitz. Then it jumps to Francis, still solemn and solitary, sitting, head bowed, in a darkened cell in the camp—an evocation of Jesus weeping over Jerusalem. Staged for the camera, and in the wake of harrowing archival scenes from the camp, this is one of the more shameless episodes in a dishonest movie. Francis’ coolness toward Israel drains the scene of any content other than Bergolian Weltschmerz.

A Contradiction Between Image and Action

Clichéd vignettes follow each other like beads on a string. Humble Francis kisses feet; paternal Francis enjoys the drawings in his 2016 children’s book; tender Francis pats the heads of the sick. Catch a glimpse of the pope at the side of Stephen Hawking. Admire his sweet reasonableness with heads of state. Marvel at standing ovations earned on the world stage.

A telling moment occurs in an African hospital. A palsied man lies unresponsive in bed while Francis leans over to touch his head. Suddenly an attendant darts forward to pull back his blanket, exposing the patient’s hand in tremor to highlight the pathos. She throws a quick look at the camera. This is a photo op after all.

Linking the kaleidoscope of scenes is Wenders’ talking head format. In one self-flattering segment, Francis over-performs. He tells a maudlin anecdote about calling, at a mother’s request, an eight-year-old boy dying of cancer. After several attempts to speak to the child, Francis leaves his voice on the family answering machine and, mirabile dictu, the boy died “reconciled to his own death.”

Not having spoken to the boy, how would he know? In fiction, the death of Little Nell was risible in its strain to pull heart strings. In real life, and from the lips of a self-aggrandizing pope, its replay is obscene.

Francis’ expressed concern for a single doomed child did not extend here to the unborn. Francis kept silent in the lead-up to Ireland’s referendum on abortion, a defining issue of our time. Released just ahead of the vote, the movie contains not a word in witness to the dignity of life in the womb.

A Simulation of Personal Intimacy

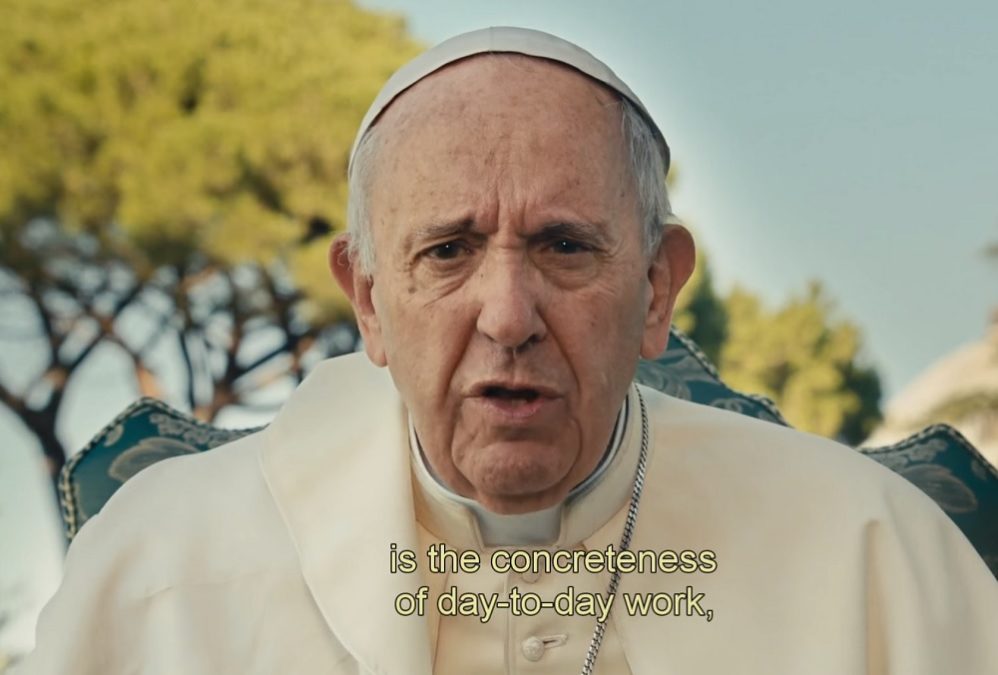

Wenders effectively uses Errol Morris’ trademark Interrotron, a rigged device for creating an illusion of the interviewee’s emotional accessibility. In the hypnotic light of the screen, Francis appears to be eyeball-to-eyeball with each viewer.

The purpose of ‘Pope Francis’ is not to inform but to create an aura.

Looking at the Interrotron, Francis talked to Wenders’ face on the screen in front of him. In reality, Wenders was 20 meters (about 65 feet away) and wearing ear phones. The device elicits changes in facial expression and gestures that are absent when the subject of an interview looks into a blank camera lens.

The medium has, indeed, become the message. The device’s simulation of personal intimacy possesses a power unrivaled by standard filmic means. It lends an appearance of solidity to unctuous generalities and ideological boilerplate.

The purpose of “Pope Francis” is not to inform but to create an aura. Francis is an avuncular messiah who reminds us to slow down and play with our children. Have a sense of humor. And don’t forget to smile: “A smile is the flower of the heart.” Banal sugar water hints at the level of lay sensibility Francis courts and encourages.

We are all “children of Abraham.” We worship the same God; we are all one family, and Jesus is “our older brother.” Divisive truth claims have no place in the religious equivalent of light opera. Francis channels Gilbert and Sullivan: “Nevermind the why and wherefore, / Love can level ranks, and therefore . . .” (“Pirates of Penzance”) What levels ranks can level dogma. And that is his end game. Francis is not restoring the church but de-Christianizing it

Pope Francis Planned This As Soon as He Took Office

“Pope Francis” is a disturbing film, not solely for its exaltation of Francis and his politics but more so for having been planned from the beginning of his ascent to office. Biography.com states that Wenders received a written invitation to “collaborate” with Pope Francis on a documentary about his pontificate in 2013, the year his papacy began. Wikipedia sets the date in 2014. (The Vatican press office was quick. Just released, the film already has a Wiki entry, as if it were a classic in cinema history.)

Bergolio was intent on documenting himself as the hero of his own pontificate early on.

Dario Edoardo Viganò, an Italian priest dedicated to the semiology of cinema and audio visual, initiated work between Francis and the filmmaker. A friend of Wenders since they met at the 2004 Venice Film Festival, Viganò was the Vatican’s first envoy to the Cannes film festival in 2015. In that year, Francis founded the Vatican’s Secretariat for Communications, naming Viganò its first prefect.

This is crucial: Bergolio was intent on documenting himself as the hero of his own pontificate early on. Accordingly, the commissioned film subordinates the substance of the papacy to Francis’s personality and secular pieties. “He is the shepherd of the whole world. His life itself is a sermon,” an elderly friend tells the camera.

Where to close? Secretariat for Communicatons is an urbane surrogate for Ministry of Truth. It is all in the wording. The rest is spectacle, carrying us along on a wave of images. Emotion-inducing visuals triumph over words and reason. Designed to promote the cult of personality, “Pope Francis” makes an idol of the pope and shrinks Christianity to just another ideology.

Maureen Mullarkey is an artist who writes on art and culture. She keeps the weblog Studio Matters.

Follow her on Twitter, @mmletters.

Photo 60 Minutes / YouTube

Source

No comments:

Post a Comment