March 20, 2019

7 Min Read

By: Aysha Khanayshabkhan

Left: The Assalam Center of Boca Raton, Fla. Right: Walnut Hill Community Church in Bethel, Conn. Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

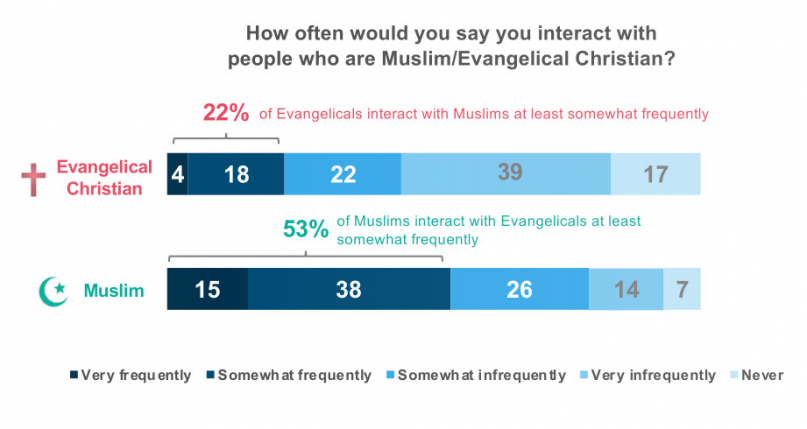

(RNS) — As a growing number of evangelical Christian leaders are working to improve Christian-Muslim relations, a new online study finds that more than 3 in 4 U.S. evangelicals say they never or infrequently interact with Muslims.

The national benchmark survey by the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding — which conducted online interviews with 500 self-identified Muslims and 500 self-identified evangelicals in early January — suggests that an overlap in religious values between the two faith groups is obscured by a lack of understanding.

Rabbi Marc Schneier, who heads the foundation, said he was surprised at the low number of evangelical Christians — 22 percent — who said they interact with Muslims at least somewhat frequently and that they believe the interaction has fostered better understanding between the groups. In contrast, 53 percent of Muslims said the same for evangelicals.

(RNS) — As a growing number of evangelical Christian leaders are working to improve Christian-Muslim relations, a new online study finds that more than 3 in 4 U.S. evangelicals say they never or infrequently interact with Muslims.

The national benchmark survey by the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding — which conducted online interviews with 500 self-identified Muslims and 500 self-identified evangelicals in early January — suggests that an overlap in religious values between the two faith groups is obscured by a lack of understanding.

Rabbi Marc Schneier, who heads the foundation, said he was surprised at the low number of evangelical Christians — 22 percent — who said they interact with Muslims at least somewhat frequently and that they believe the interaction has fostered better understanding between the groups. In contrast, 53 percent of Muslims said the same for evangelicals.

Graphic courtesy of the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding

In addition, the poll’s open-ended questions, which weren’t released with the survey results, showed that many evangelicals were disinterested in knowing more about Islam, its practices and holidays, according to FFEU’s polling experts, pointing to an overall lack of engagement.

Said Schneier, “That lack of interest is a real concern and a challenge.”

Among the evangelicals surveyed, most showed low levels of familiarity with basic Islamic terminology. Only half said they were very or somewhat familiar with the holy month of Ramadan — about 3 percent incorrectly identified it as a Jewish term — and 9 percent were familiar with the holiday of Eid al-Fitr.

Muslims tended to show more understanding of Christian terms, with 65 percent surveyed saying they were familiar with Lent and 77 percent saying the same of the Old Testament.

The data “reveals much about our current state,” said Micah Fries, co-author of “Islam and North America: Loving Our Muslim Neighbors.” “Unfortunately, too often it is fear and ignorance that fuels further separation between the Muslim and Evangelical communities.” The knowledge gap shown in the survey, he said, might serve as “a wakeup call” that could lead to better relations.

The study provided support for that possibility: Muslims and evangelicals who interacted with members of the other group frequently were more likely to see their faiths as more similar than different and to perceive the other faith as inclusive, modern and evolving.

“Evangelical Christian-Muslim relations is today’s largest interreligious challenge, and the poll shows that there are causes for concern and elements of hope and optimism on both sides to narrow the divide,” Schneier said.

|

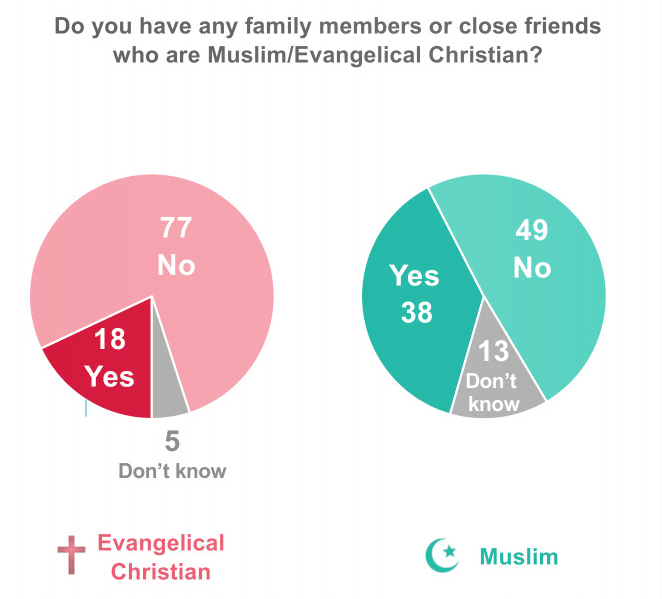

Graphic courtesy of the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding

As a result, the Foundation for Ethnic Understanding, founded in 1989 to address Muslim-Jewish relations and African-American-Jewish relations, has made it a priority this year to help build relationships between Muslims and evangelicals.

Yet there was cause for concern: 62 percent of evangelicals surveyed identified “a lot” or “some” anti-Muslim sentiment among evangelicals.

Common reasons given for the discrimination was a feeling that Islam is insular and parochial, and that Muslims are largely anti-Israel.

The FFEU’s survey found that more than half of surveyed Muslims and evangelicals blame both Israelis and Palestinians for the Mideast crisis and strong numbers of both groups said they were hopeful for a peaceful solution.

The survey also revealed that Muslims and evangelicals share many religious and political values. Religious freedom, immigration, health care and the safety of their families were among both groups’ top political concerns. Both groups said they pray and attend faith services at similar rates, and they also ranked the same three religious values as most important to them: daily prayer, family and making the world a better place.

If evangelicals don’t see these similarities, said Imam Ossama Bahloul, resident scholar at the Islamic Center of Nashville, it’s because of their lack of exposure to the Islamic faith.

“Most of the evangelicals lack an opportunity to interact with the Muslim community,” he said. “One might say that they live within their own bubble of like-minded people, and this has prevented them from realizing that there are similarities between both themselves and Muslims. Both communities care deeply about faith, family and are pro-life.”

That ignorance prevents them from building coalitions to further their commonly held values, said Bahloul, who has been working on strengthening interfaith relations in Tennessee for nearly a decade.

He said that while his community’s relationship with local Jews is thriving, building ties with evangelical leaders has been “challenging.” Evangelical leaders are willing to work together outside their respective houses of worship, but giving imams access to their congregations was another issue.

But continued Muslim outreach to evangelicals and rural Americans is the “most critical work we have to do in America,” he said. “We have to give it the proper attention, to change the narrative, to fight Islamophobia and any discrimination against religious minorities.”

Eboo Patel, a prominent Muslim interfaith advocate, says FFEU’s data misses an emerging trend in which growing numbers of evangelicals and institutions are mobilizing to bridge the Christian-Muslim divide.

In February, a large contingent of evangelical leaders joined other interfaith leaders at the Alliance of Virtue conference advocating religious freedom in Washington, D.C. In Texas, NorthWood Church’s pastor Bob Roberts Jr. has led initiatives to bring together pastors and imams. Fuller Theological Seminary professor Matthew Kaemingk has written a book about Christian hospitality toward Muslim immigrants.

Last year, Neighborly Faith, an organization in North Carolina working to help evangelicals build relationships with people of other faiths, launched a fellowship program with funding from Islamic Relief USA to help evangelical college students combat Islamophobia in their communities. One fellow, a student from Chicago’s Trinity International University, is bringing together families from his church and families from a local mosque to break bread together. Another fellow, from the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, is working to help Southern Baptists welcome Muslim refugees.

The divide, Patel said, “is inspiring a set of Muslims and evangelicals to be interfaith leaders to bridge that gap,” Patel said. “They’re recognizing that fear and loathing of Muslims is a civil problem and a violation of their faith commitments.”

Author Eboo Patel. Image courtesy of Interfaith Youth Core

Nowhere is the phenomenon more visible, Patel said, than in evangelical higher education and among young evangelicals. In the past several months, he has been invited to speak at prominent Christian universities, including Wheaton, Pepperdine and Bethel.

“They’re saying, ‘Look, we cannot bear false witness against our Muslim neighbor,’” Patel said. “They’re recognizing that it’s not good for them, it’s not good for America, and it’s not Christian.”

When the FFEU conducted a similar study on Jewish-Muslim relations last year, the findings were more positive. Majorities of both Muslims and Jews agreed that their faiths are more similar than different, and more than 60 percent of both Muslims and Jews said that working together to strengthen anti-discrimination policies is important.

Such numbers are the “fruit of long-term bridge-building,” said Patel, adding that political climates with rampant anti-Semitism and Islamophobia have drawn Jews and Muslims, both religious minorities, together in common cause. White evangelicals, however, are in a position of relative power — courted by the president and with open access to the White House. Bahloul said their size and influence mean that many evangelical Christians do not seem to realize that interfaith work is in their interest.

“I know from my sincere relationships with evangelicals that building relationships between the two communities serves to benefit on an individual level as well as the community at large,” he said.

Schneier sees Jewish-Muslim relations in the United States as a roadmap for evangelicals.

“Jewish-Muslim relations have moved from a state of conflict to a state of cooperation,” Schneier said. “I’ve seen this trajectory toward the promised land of Jewish-Muslim cooperation, and I predict this same journey will happen for evangelical Christians.”

The margin of error for respondents in the FFEU survey is plus or minus 4.38 percentage points.

No comments:

Post a Comment