Amid increasing polarization and shifting church trends, the black church continues to speak out on matters of justice.

Kate Shellnutt November 15, 2019 9:05 AM

Image: The Washington Post / Contributor / Getty

Hundreds gathered in a Chicago sanctuary last night to hear Christian leaders calling on believers to engage the political process and advocate for their convictions in the election year ahead.

The Faith and Politics Rally was organized by the And Campaign, a nonpartisan group that says Christians have a “particular obligation” to provide moral leadership and seek the common good—an approach that has become increasingly contentious in the US.

A majority of Americans believe churches should “keep out” of politics, according to a survey released today by the Pew Research Center. Evangelicals and Protestants from historically black churches—both represented at the recent rally—are the only major religious traditions that still want faith communities to “express their views” on social and political issues.

“While a misappropriation of the separation between Church and State has sometimes been used to suggest people of faith are the only people who can’t consider their values when participating in politics, we know that both our faith and the demands of citizenship require that we bring our full selves to the project of self-governance,” And Campaign leaders declared in their 2020 presidential election statement.

Evangelicals (in this survey, a multiethnic sample) and historically black Protestants tend to rank as most devout among religious groups in the US. They share core theological beliefs and a corresponding desire to see those beliefs shape their lives and communities. Evangelicals and black Protestants are the two traditions that consider their faith the most important source of meaning in their lives. But they often come from different racial and cultural contexts as they consider how to apply it to the political realm.

According to Pew, black Protestants are the most likely to say churches don’t have enough influence in politics (54%), compared to 48 percent of evangelicals and 28 percent of Americans overall.

“It’s less about politics in the electoral sense … and more of a sense of black folks seeing faith as a way to rectify and address issues of injustice,” said Jason Shelton, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Arlington whose research focuses on the black church. “The separation of realms (faith and politics) is clear for white evangelicals much more than it is for African American Protestants, even though they have the same heightened religious sensibilities.”

“There’s sense of right and wrong in a moral sense that’s been fused together … The pulpit has inspired us to say, ‘This is the direction we gotta move for social change, to create a better day.’”

Politics at the pulpit

For generations, African Americans have relied on their faith and the church in the midst of injustice, oppression, and suffering. And the black church has played a unique role in addressing community needs and fostering leaders to advocate for change.

“For many years, the African American preacher was more than just a preacher in the community. The preacher was also the person who was the most educated, the most knowledgeable, and had to know the pulse of the community. They were the people the community looked to not only for spiritual guidance, but especially during the civil rights era, the 1960s, the African American pastor became the African American politician in many ways.”

Black Protestants (45%) are about twice as likely as Americans on average (23%) to say churches should endorse candidates, according to the latest Pew survey. In 2016, the researchers found black Protestants were far more likely to hear pastors mention either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump in their sermons.

Most Americans and most Christians continue to oppose churches officially endorsing candidates. It remains illegal for tax-exempt charities to do so, though President Trump has repeatedly brought up repealing the Johnson Amendment.

“I deliberately avoid using language that is too precise,” said Brandon Washington, preaching pastor at The Embassy Church in Denver. “You’ll never see us endorsing a candidate or anything like that.”

Washington is an African American, and his multiethnic church is just over half white. Along with the racial diversity, his congregation contains members of both parties. He addressed tension after the last presidential election with a sermon from Psalm 72, which begins, “Endow the king with your justice, O God …”

“Falling in line with a theory of politics that’s consistent with the African American church, my decision to not make political statements or not align with a political party from the platform does not keep me from addressing matters that I believe have become politicized,” including abortion and racism, Washington said.

Faith in the parties

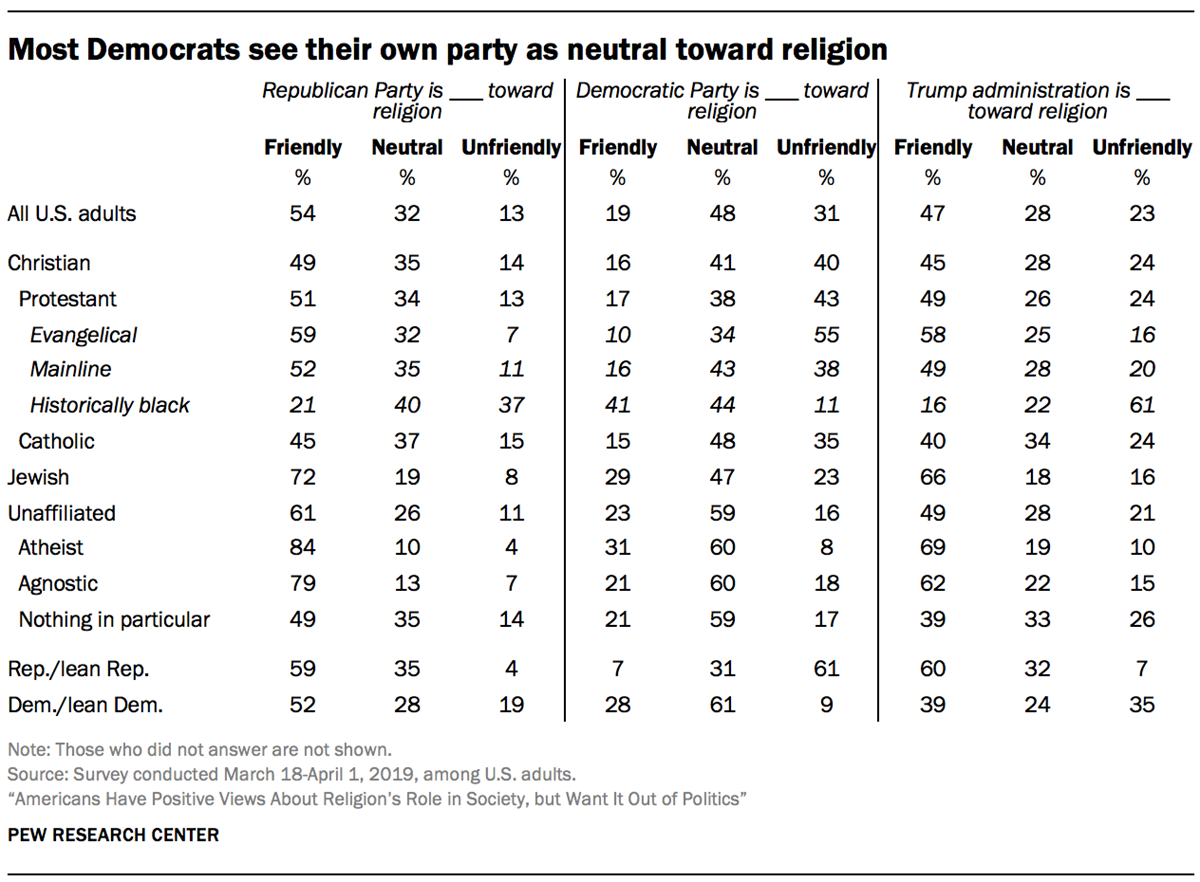

Despite all they have in common, evangelicals overall and those in historically black churches have leaned toward opposite sides of the political spectrum. A majority of evangelicals view the Republican Party (59%) and President Trump (58%) as friendly to religion, but few black Protestants agree, Pew reported. About 1 in 5 (21%) consider the Republican Party friendly to religion, and 1 in 6 (16%) say that the president is.

Many black Protestants fail to see the spiritual fruit of the Christian convictions employed by Republicans and actually want to see more faith engagement on the political right. In the Pew survey, 37 percent of black Protestants, a plurality, said religious conservatives have “too little” control of the Republican Party—more than the 28 percent of evangelicals and 18 percent of mainline Protestants who said the same.

This year has also brought renewed attention to the Religious Left, with some commentators making the case that Democratic candidates should do more to address people of faith in particular. Just 16 percent of mainline Protestants and 15 percent of Catholics consider the Democratic Party friendly to religion. Black Protestants, though, are relatively satisfied; 41 percent of them rated Democrats’ approach to faith positively.

Because of the tradition of political engagement and dialogue in black churches, though, black voters are more eager to find a politician who addresses their concerns than one who only references their faith, according to Chris Butler, pastor of Chicago Embassy Church.

“Black folks have been participating in politics in a fairly savvy way, and I don’t think black Christians are looking to their political leaders for faith leadership. On the one hand, we see the two intertwined, but that’s more so in the community,” he said in an interview with CT. “We’re looking at what person, what party is going to most impact those issues.”

Butler, like fellow speakers at the And Campaign event, emphasized putting Christian convictions first.

“It is okay to be partisan. It is not okay to put partisanship above our faith,” he said. “We can be partisan, but we have to challenge our party from the position of our faith versus putting the party first and subordinating our Christian faith and our biblical beliefs to a party.”

Though some black evangelicals have been outspoken against the party’s pro-choice policies or other issues of disagreement, they tend to be in the minority. But political shifts are taking place, according to Shelton’s sociological research, as more African American Christians opt to attend nondenominational churches rather than the traditional Baptist and Methodist congregations.

“Black nondenoms are three times more likely to vote Republican than other groups,” said Shelton, author of the forthcoming book Death of the Black Church: How Religious Diversity Erodes Racial Solidarity. “This is sort of the melting pot in action. You have some black folks that are moving away from the traditional church, embracing the faith still, embracing Christianity in a less black context … and moving into a more racially mixed or predominantly white congregation.”

Washington, who leads a racial mixed congregation, continues to look to the black church’s witness. Going into 2020, he sees black Christians demonstrating the importance of taking a stand for their biblical convictions and leading faithfully from the margins.

“The body of believers should participate in the government and its political structures. My concern though is that we are going to make culture by making laws or putting politicians in office, and that’s a secondary or maybe tertiary approach to cultural influence,” he said. “I think that the church should recognize itself as the most authoritative voice … instead of relegating it to a vote and letting politicians who do not necessarily espouse our same evangelical perspectives be the ones to do that for us.”

No comments:

Post a Comment