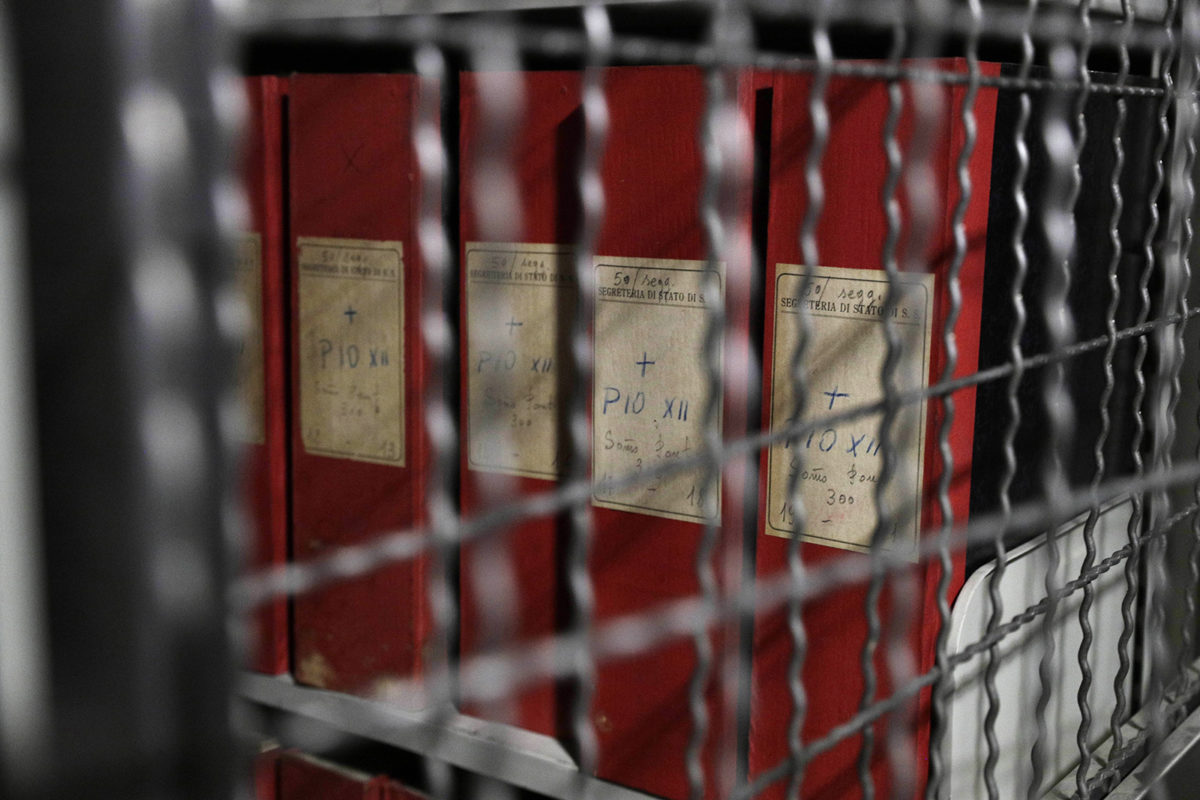

Folders marked with labels reading “Pius XII" are seen through a grating during a guided tour for media of the Vatican library on Pope Pius XII, at the Vatican, Thursday, Feb. 27, 2020. The Vatican’s apostolic library on Pope Pius XII, the World War II-era pope and his record during the Holocaust, opened to researchers on March 2, 2020. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

April 27, 2020

Tom Heneghan

PARIS (RNS) — The long-awaited opening of Pope Pius XII’s wartime records only lasted a week before the coronavirus shut the Vatican archives down again, but that was long enough for documents to emerge that reflect badly on the pontiff accused of silence during the Holocaust, according to published reports.

In that week alone, German researchers found that the pope, who never directly criticized the Nazi slaughter of Jews, knew from his own sources about Berlin’s death campaign early on. But he kept this from the U.S. government after an aide argued that Jews and Ukrainians — his main sources — could not be trusted because they lied and exaggerated, according to the researchers.

The researchers also discovered the Vatican hid these and other sensitive documents presumably to protect Pius’ image, a finding that will embarrass the Roman Catholic Church still struggling with its covering up of the clerical sexual abuse crisis.

These reports are coming out in Germany, home to seven researchers from the University of Münster who went to Rome despite the coronavirus crisis there for the historic opening of Pius’ wartime papers on March 2. Other researchers from the United States and Israel had been expected to attend the opening but apparently stayed home because of the pandemic.

READ: A gift of photos from a papal coronation opens a path for Jewish-Catholic healing

Leading the German team was Hubert Wolf, 60, a historian of the Catholic Church who has researched in the Vatican’s Secret Archive — now called the Apostolic Archive — since his student days. A Catholic priest and prolific author, he enjoys a reputation as an objective researcher and outspoken analyst.

“We have to first check these newly available sources,” he told Kirche + Leben, the Catholic weekly in Münster, last Friday. “If Pius XII comes out of this study of the sources looking better, that’s wonderful. If he comes out looking worse, we have to accept that, too.”

The stakes are high.

Tom Heneghan

PARIS (RNS) — The long-awaited opening of Pope Pius XII’s wartime records only lasted a week before the coronavirus shut the Vatican archives down again, but that was long enough for documents to emerge that reflect badly on the pontiff accused of silence during the Holocaust, according to published reports.

In that week alone, German researchers found that the pope, who never directly criticized the Nazi slaughter of Jews, knew from his own sources about Berlin’s death campaign early on. But he kept this from the U.S. government after an aide argued that Jews and Ukrainians — his main sources — could not be trusted because they lied and exaggerated, according to the researchers.

The researchers also discovered the Vatican hid these and other sensitive documents presumably to protect Pius’ image, a finding that will embarrass the Roman Catholic Church still struggling with its covering up of the clerical sexual abuse crisis.

These reports are coming out in Germany, home to seven researchers from the University of Münster who went to Rome despite the coronavirus crisis there for the historic opening of Pius’ wartime papers on March 2. Other researchers from the United States and Israel had been expected to attend the opening but apparently stayed home because of the pandemic.

READ: A gift of photos from a papal coronation opens a path for Jewish-Catholic healing

Leading the German team was Hubert Wolf, 60, a historian of the Catholic Church who has researched in the Vatican’s Secret Archive — now called the Apostolic Archive — since his student days. A Catholic priest and prolific author, he enjoys a reputation as an objective researcher and outspoken analyst.

“We have to first check these newly available sources,” he told Kirche + Leben, the Catholic weekly in Münster, last Friday. “If Pius XII comes out of this study of the sources looking better, that’s wonderful. If he comes out looking worse, we have to accept that, too.”

The stakes are high.

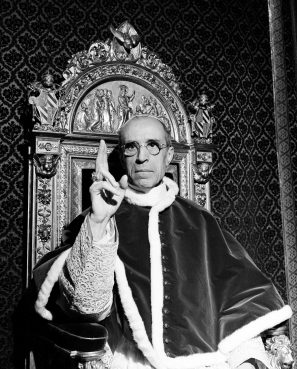

In this file photo dated Sept. 1945, Pope Pius XII, wearing the ring of St. Peter, raises his right hand in a papal blessing at the Vatican. (AP Photo, File)

Pius XII, who headed the Catholic Church from 1939 to 1958, was the most controversial pontiff of the 20th century. His failure to denounce the Holocaust publicly earned him the title of “Hitler’s pope,” and critics — especially among Jewish historians, but not only them — have for decades asked for his wartime archives to be opened for scrutiny.

The pope’s defenders have long argued he could not speak out more clearly for fear of a Nazi backlash and cite his decision to hide Jews at the Vatican and in churches and monasteries as proof of his good deeds. They note the Vatican had already published an 11-volume series of documents selected from his archives to prove his innocence.

A joint Catholic-Jewish commission that was launched in 1999 to seek to resolve this case broke up two years later because the Vatican would not open up its archive, which was supposed to stay sealed until 2028.

Now the archive has been opened, and the Münster team of researchers has begun to publish its first findings; they do not look good for Pius or the Catholic Church. The details are a bit complicated, but Wolf’s conclusions are quite clear.

The chain of events goes back to September 27, 1942, when a U.S. diplomat gave the Vatican a secret report on the mass murder of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto. It said about 100,000 had been massacred in and around Warsaw and added that another 50,000 were killed in Lviv in German-occupied Ukraine.

The report was based on information from the Geneva office of the Jewish Agency for Palestine. Washington wanted to know if the Vatican, which received information from Catholics around the world, could confirm this from its own sources. If it could, would the Vatican have any ideas about how to rally public opinion against these crimes?

The archive included a note confirming that Pius read the American report. It also had two letters to the Vatican independently corroborating the reports of massacres in Warsaw and Lviv, according to the researchers.

A month before the American request, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic archbishop of Lviv, Andrey Sheptytsky, had sent Pius a letter that spoke of 200,000 Jews massacred in Ukraine under the “outright diabolical” German occupation.

In mid-September, an Italian businessman named Malvezzi told Mgr. Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, of the “incredible butchery” of Jews he had seen during a recent visit to Warsaw. Montini reported this to his superior, the Vatican’s secretary of state (prime minister), Cardinal Luigi Maglione.

But the Vatican told Washington it could not confirm the Jewish Agency report.

The basis for this, Wolf told the Hamburg weekly Die Zeit, was a memo by another staffer at the Secretariat of State, Fr. Angelo Dell’Acqua, who later became a cardinal. In that memo, he warned against believing the Jewish report because Jews “easily exaggerate” and “Orientals” — the reference is to Archbishop Sheptytsky — “are really not an example of honesty.”

That memo is in the archive but was not included in the 11-volume series of wartime documents the Vatican published to defend Pius’ reputation. “This is a key document that has been kept hidden from us because it is clearly anti-Semitic and shows why Pius XII did not speak out against the Holocaust,” Wolf told Kirche + Leben.

Men, women and soldiers gather around Pope Pius XII, his arms outstretched, during his inspection tour of Rome, Italy, on Oct. 15, 1943, after the Aug. 13 American air raid in World War II. (AP Photo, File)

Wolf said the 11-volume series, known to historians as the “Actes et Documents” after its French title, took some documents out of their chronological order and thereby made it hard if not impossible to understand them in context.

“That’s why we have to be skeptical about the whole 11-volume series and check it against the archive document by document,” he said. “These 11 volumes break up the context in which the documents are found in the archive. The result is that one can no longer understand how they relate to each other.”

The research team also found three small photographs showing emaciated concentration camp inmates and corpses thrown into a mass grave. A Jewish informer had given them to the Vatican ambassador, or nuncio, in neutral Switzerland to send to the Vatican, and the Holy See confirmed reception of them in a letter two weeks later.

Wolf told the German Catholic news agency KNA that another potentially embarrassing issue was the so-called “Rat Line,” an informal network that helped former top Nazis escape from central Europe to Italy and from there to South America.

It has long been known that the Catholic Church — possibly with covert U.S. assistance — helped ex-Nazis, like the Holocaust bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann, concentration camp doctor Josef Mengele or Gestapo officer Klaus Barbie, flee to South America. These men were anti-communists, and both Rome and Washington considered communism their enemy.

Reports from the papal nuncio in Buenos Aires could indicate a Vatican role in the Rat Line, Wolf told KNA. “What did he know about this activity?” he asked. “The Vatican might have been able to get them passports … was the nuncio the middle man? Did the Argentine embassy in Rome do all the work?

“We’re just asking open questions, and have to be ready for any kind of answer,” he said.

Other questions Wolf wants to research are Pius’ relations with U.S. political and intelligence networks during and after the war, his role in promoting European unity, and his thoughts about allying with Muslims in a campaign against communism.

Answers to these and other questions could also influence a drive by conservative Catholics to have Pius declared a saint. Wolf serves as a historian for this cause and says it will take years to assess his career.

The archive will remain closed at least until this summer, which Wolf considers a catastrophe for his research project. “We could figure on seven researchers before. Can this continue in the autumn?” he asked.

“There are enough questions to keep the whole team busy for 10 years!”

No comments:

Post a Comment