Scandals have taken a toll, and faith is flagging in Europe and the U.S. But Catholicism isn’t on the wane—it’s changing in influential ways.

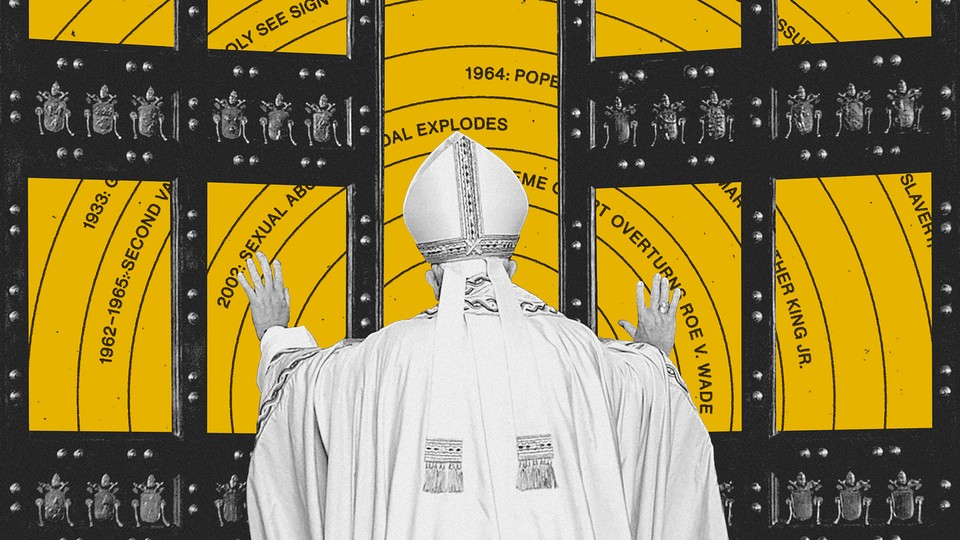

Photo-illustration by Chantal Jahchan. Source: Vatican Pool / Getty.

DECEMBER 11, 2022, 7 AM ET

In may 2021, a time when public gatherings in England were strictly limited because of the coronavirus pandemic, the British tabloids were caught off guard by a stealth celebrity wedding in London. Westminster Cathedral—the “mother church” of Roman Catholics in England and Wales—was abruptly closed on a Saturday afternoon. Soon the groom and bride arrived: Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Carrie Symonds, a Catholic and a former Conservative Party press officer with whom he had fathered a child the previous year. A priest duly presided over the marriage, despite the fact that the Catholic Church opposes divorce and sex outside marriage, and that Johnson had been married twice before and had taken up with Symonds before securing a divorce. It was an inadvertently vivid display of the Church’s efforts to accommodate its teachings to worldly circumstances.

That same month, Church-state relations in the United States took a fresh turn when the Supreme Court decided to hear a case from Mississippi that challenged the legal right to abortion recognized in Roe v. Wade. The Court’s decision reflected the power of its conservative majority, whose six members include five traditionalist Catholics. And it augured an eventual victory in a 50-year campaign against legal abortion, a movement anchored from the start in the Church teaching that life begins at conception—an absolute position on an issue that ordinary Catholics, like most other Americans, disagree about. The victory came this past June, when the Court struck down the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Together, these episodes point up an incongruous recent development: the Catholic Church’s assertive presence in public life even as Catholic faith and practice recede in families, schools, and neighborhoods in America and across Europe. As John T. McGreevy observes in Catholicism: A Global History From the French Revolution to Pope Francis, signs that the Church has lost vitality are abundant. Europe has seen parish closures, shrinking numbers of priests, dwindling attendance at weekly Mass, and steady departures from the faith. In the U.S., more than a third of people raised Catholic “no longer identify as such.” The clerical sexual-abuse scandals have ravaged the Church’s credibility, cost it billions of dollars, and put some of its leaders under criminal investigation.

At the same time, a rich variety of evidence suggests that Catholicism isn’t on the wane; it’s just changing. In recent decades, the pope—first John Paul II, then Benedict, and now Francis—has become a ubiquitous global figure, made so through jet travel, mass media, and a cult of personality. The view of “human dignity” framed in the 1930s by the Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain—and enshrined in a United Nations declaration in 1948—has become a benchmark for international law and human-rights efforts. Africa, once seen as “pagan” missionary territory, is now home to a sixth of the world’s Catholics—230 million people—and “high birth rates and high rates of adult conversion,” McGreevy writes, “mean that African influence within the global church will continue to grow.” In the U.S., the recent arch-Catholic remaking of the high court is likely to shape public policy for decades.

McGreevy, a practicing Catholic and the provost of the University of Notre Dame, is well placed to offer perspective on the Church as an institution at once teetering and thriving. He’s also a historian of Catholicism and has made its interactions with civil society a theme, one he approaches with an evenhandedness rare in the field. After Parish Boundaries (1996)—an account of race relations in various urban dioceses in the U.S. over five decades—he considered the country as a whole in Catholicism and American Freedom (2003). In American Jesuits and the World (2016), he extended his reach to Latin America.

Now taking the Church’s global presence as his subject, McGreevy has written a lucid narrative of two and a half centuries of history, structured rather like a Ken Burns–Lynn Novick documentary. The chapters proceed in chronological sequence, organized around themes: the suppression of Catholicism in the 1700s, followed by its revival over the next hundred years; the Church’s dealings with empire, democracy, and nationalism in the early 20th century; the post–Vatican II turmoil over birth control, priestly celibacy, and the “dechristianization” of Europe; and finally Pope Francis’s application of Catholic teachings to such global problems as rising economic inequality and climate change. It’s a book designed to provide a “savvy baseline,” McGreevy writes, as Catholicism is “reinvented” in the years to come.

The standard narrative of the Church over the past two centuries depicts an institution dead set against the modern world abruptly swerving to embrace it. That narrative is simplistic, and McGreevy complicates it. His working idea is that Catholicism began its encounter with the modern world well before Pope John XXIII, in opening the Second Vatican Council in 1962, asked the bishops assembled in Rome “to ignore ‘prophets of doom’ who saw in ‘modern times nothing but prevarication and ruin.’ ” In McGreevy’s telling, the shifting began in 1789. The French Revolution produced a government hostile to Catholicism and sparked the revolutions of 1848 that in turn shaped the modern nation-state. Ever since, the Church has been engaged in a struggle to address social, moral, and political developments while maintaining a consistent religious identity.Over time, hostility to modern ideas became the default position of an institution that cleaved to an image of itself as unchanging.

The first third of the book explores how the Church, in the decades after 1789, dogmatically opposed modernity, while making practical accommodations to the changing societies in which its members lived. Pope Pius VII signed a concordat with Napoleon (whose troops controlled Rome) and traveled to Paris for his coronation as emperor in 1804. Yet newly cut off from state power and dismayed by the Enlightenment’s stress on individualism, Catholic leaders in France, especially, responded to an urbanizing industrial age by erecting what McGreevy calls a “milieu” of schools, seminaries, hospitals, and orphanages as a rigidly ordered parallel world set against unruly civil society. Those “Reform Catholics” (McGreevy’s term) who did strive to fit their local churches into the new order of nation-states met with resistance from the “ultramontanists,” who regarded the pope as a pan-European absolute monarch and the Church as a bulwark against surging democracy.

The conflict came to a head at the First Vatican Council, in 1869. McGreevy cites a French observer’s account of the gathering’s anti-worldly spirit: “The church, through its supreme pastor, says to the lay world, to lay society, and to lay authorities: It is apart from you that I want to exist, to take action, to make decisions, and to develop, affirm, and understand myself.” The ultramontanists prevailed, and the Catholicism then exported to the Americas through mass emigration was leery of democracy—and of citizens’ efforts to expand the right to vote to women and to allow moral issues to be decided by majority rule (or vulgar haggling in the statehouse).

Over time, hostility to modern ideas became the default position of an institution that cleaved to an image of itself as premodern and unchanging. Again and again, the Church’s certainty about what it was against clouded its sense of what it should support, as it adapted to circumstances in ways that seem glaringly inconsistent today. Although the Church criticized the slave trade in Africa, Catholic leaders were slow to support the abolition of slavery in the United States—“so opposed were they to the individualist (at times anti-Catholic) rhetoric they associated with liberal Protestant or secular abolitionists,” McGreevy writes. They fiercely denounced anti-Catholic quotas and discrimination in the United Kingdom, where Anglicanism was the state religion; meanwhile, they ensured that the new republics in Latin America recognized Catholicism as the “national religion,” and often condoned exclusionary practices against Jews and Protestants. Strangely, the Church lined up against both industrial capitalism and working-class socialism—with many Catholics believing that both were controlled by Jews.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 prompted the Church to recognize democracy as a form of government more favorable to belief than atheistic communism was. But the Church’s rejection of Bolshevism led it—in enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend style—to back unjust regimes: Mussolini’s Fascists in Italy, Franco’s Falangists in Spain (where the Loyalists were violently anti-Catholic), and the Nazi Party of Adolf Hitler, whom the Vatican praised for his anti-Bolshevism before adopting its notorious neutrality during World War II. “In majority Catholic states such as Brazil, Portugal, and Austria,” McGreevy observes, politicians and Church leaders together articulated “a distinct Catholic authoritarian vision,” made up of “a fierce anti-communism, an underlying drumbeat of anti-Semitism, and skepticism about democratic politics.”

After the war, the Church boosted Christian Democratic parties in Italy, France, and Germany; endorsed an independence movement led by the Catholic Léopold Senghor in Senegal; backed the Catholic Ngô Ðình Diệm’s postindependence regime in South Vietnam; and propped up antidemocratic oligarchies in Latin America—all as fire walls against communism. It kept up its opposition to postwar stirrings of inclusion—of Catholics in public schools, women in the workplace, sex in the movies.

Yet great ferment was under way in Catholic intellectual life, as theologians at still-robust seminaries in Europe merged Church traditions with continental philosophy. New approaches to liturgy (shifting from Latin to vernacular languages), biblical interpretation (undertaking fresh scrutiny of the Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic sources), and interreligious dialogue (challenging the idea that Catholics were duty-bound to oppose other faiths) thrived. In response, John XXIII called the world’s Catholic bishops to Rome for reflection on the state of the Church in an ecumenical council—Vatican II—and appointed vanguard theologians to advise them.

As the council progressed from 1962 to 1965, the image of Catholicism as a bulwark against modernity was replaced by a vision of a “pilgrim Church” providing humble service to a world in which war, migration, the spread of state-sponsored atheism, and rapid changes in technology had left people desperately in need of a religious perspective. It was time, in McGreevy’s words, “for Catholics and the church to take on the world’s problems as their own,” living their faith (as Pope John had proposed) “in such a way as to attract others less by doctrine than ‘by good example.’ ”

Soon “the world rushed in”: the Cuban missile crisis, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the birth-control pill, the cresting of the movement for Black civil rights. Pope John’s successor, Pope Paul VI, met with Martin Luther King Jr.—over the objections of Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York, who was suspicious of Communist leanings among civil-rights activists. Catholics marched for peace, priests ran for office, and black-clad nuns adopted plain dress and went to graduate school.

The vatican’s opposition to modernity had given Catholics a common adversary to unite against, and had suppressed the Church’s internal disagreements. Vatican II brought these out into the open. Since then, an institution long defined by what it was against has had to ask itself: What is the Church for—what vision of life does it strive to fulfill?

The challenge of offering answers has fallen, at least publicly and rhetorically, to the popes, who have used the papacy to promote distinct programs for engagement with the world. John Paul II affirmed that the Church stands for “a culture of life” against a “culture of death”—taking an approach to human flourishing grounded in a fixed view of gender roles, marriage, and procreation. Benedict XVI saw the Church as the source of objective truth, opposing a “dictatorship of relativism.” Francis proposes that the Church foster “a culture of encounter,” in which people of faith thrive through face-to-face dealings with others of different backgrounds and outlooks, forging a solidarity stronger than nation, class, or ideology.On abortion, the bishops haven’t managed to convince their own people: Polls indicate that Catholics’ views are as varied as those of Americans as a whole.

Vatican II invited Catholics to do openly what they’d tried to do surreptitiously all through the modern age—adapt the Church’s practices to local circumstances where possible—and those papal programs (unfamiliar to most Catholics) have been meant to guide the bishops as they seek to influence civil society in their home countries. Unsurprisingly, consistency has not been the rule since 1965 any more than it was after 1789. Sometimes the tensions involve geopolitics: John Paul championed a people’s movement against oppressive state power in Poland while opposing people’s movements against oppressive state power in Central America. Sometimes they arise from a split between doctrine and practice: Although women now run the offices in many U.S. parishes, the sacramental theology barring women from the priesthood still prevails in Rome. And sometimes a shift in tactics is at work, as when hard-right American Catholics switched from decrying the “activist Court” that ruled in Roe v. Wade to helping form an “activist Court” rooted in traditionalist Catholic principles.

All along, the Church hasn’t been able to shake a habit of opposition to the nation-state when it is seen as running amok. In the U.S., that habit has paradoxically enabled the Church to maintain a robust public profile even as it loses its hold on ordinary believers. Catholic progressives were never so ardent, or so prominent, as when they came together in the 1970s to oppose U.S.-funded authoritarianism in Central and South America. Catholic traditionalists gained cohesion from their unwavering opposition to abortion, a cause that gathered momentum after Roe, aided by the unstinting support of American bishops, who joined fundraising dinners and blessed rallies such as the annual March for Life in Washington. Even as parish life in neighborhoods atrophied and Catholic schools closed, each movement drew headlines, styling itself as a faithful Catholic remnant valiantly standing up to worldly powers. For progressives, the struggle to thwart an anti-communist “Reagan doctrine”—a policy aligned with the Vatican’s—proved exhausting. For traditionalists, by contrast, the striking down of Roe is evidence that a clear message can win out against what they see as ever looser social mores.

The Court’s decision in Dobbs can be seen as a very public victory, too, in the Church’s long and conflict-ridden relations with the state. It’s a victory for the bishops in particular. Only a few years ago, the scandal of clerical sexual abuse—which they and their predecessors had evaded and covered up for decades—seemed to leave them stripped of moral authority. Now they have helped bring about a pronounced legal change on a vexed moral issue.

If it’s a victory, however, it’s a strange one. On abortion, the bishops haven’t managed to convince their own people: Polls indicate that Catholics’ views are as varied as those of Americans as a whole. As men vowed to celibacy, the bishops can’t lead by example on this issue, and for the most part, they haven’t tried coercion—by, say, withholding Communion from pro-abortion-rights Catholics, though that may be changing. Rather, they’ve opted to collaborate with a legal movement that is agnostic on many moral issues (capital punishment, for one, and those involving wealth and poverty), in the interest of elevating a cadre of “originalist” jurists whose rulings have made the anti-abortion position the basis for laws that restrict the rights of Americans broadly.

Strange as the victory is, though, it fits a pattern of Catholic dealings with modernity that will seem familiar from the Church’s history since 1789. The institution has set itself against one aspect of the modern state (an entrenched legal precedent, in this case) by accommodating a different one (the judicial branch, whose structure of appointed potentates resembles the Church hierarchy). The bishops have exercised the power they enjoy as leaders of a large religious community while scanting the views on pregnancy and family of millions of the faithful in that community. Once again, it’s hard to tell what the Catholic Church is for, but everybody knows what it is against.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition.

McGreevy, a practicing Catholic and the provost of the University of Notre Dame, is well placed to offer perspective on the Church as an institution at once teetering and thriving. He’s also a historian of Catholicism and has made its interactions with civil society a theme, one he approaches with an evenhandedness rare in the field. After Parish Boundaries (1996)—an account of race relations in various urban dioceses in the U.S. over five decades—he considered the country as a whole in Catholicism and American Freedom (2003). In American Jesuits and the World (2016), he extended his reach to Latin America.

Now taking the Church’s global presence as his subject, McGreevy has written a lucid narrative of two and a half centuries of history, structured rather like a Ken Burns–Lynn Novick documentary. The chapters proceed in chronological sequence, organized around themes: the suppression of Catholicism in the 1700s, followed by its revival over the next hundred years; the Church’s dealings with empire, democracy, and nationalism in the early 20th century; the post–Vatican II turmoil over birth control, priestly celibacy, and the “dechristianization” of Europe; and finally Pope Francis’s application of Catholic teachings to such global problems as rising economic inequality and climate change. It’s a book designed to provide a “savvy baseline,” McGreevy writes, as Catholicism is “reinvented” in the years to come.

The standard narrative of the Church over the past two centuries depicts an institution dead set against the modern world abruptly swerving to embrace it. That narrative is simplistic, and McGreevy complicates it. His working idea is that Catholicism began its encounter with the modern world well before Pope John XXIII, in opening the Second Vatican Council in 1962, asked the bishops assembled in Rome “to ignore ‘prophets of doom’ who saw in ‘modern times nothing but prevarication and ruin.’ ” In McGreevy’s telling, the shifting began in 1789. The French Revolution produced a government hostile to Catholicism and sparked the revolutions of 1848 that in turn shaped the modern nation-state. Ever since, the Church has been engaged in a struggle to address social, moral, and political developments while maintaining a consistent religious identity.Over time, hostility to modern ideas became the default position of an institution that cleaved to an image of itself as unchanging.

The first third of the book explores how the Church, in the decades after 1789, dogmatically opposed modernity, while making practical accommodations to the changing societies in which its members lived. Pope Pius VII signed a concordat with Napoleon (whose troops controlled Rome) and traveled to Paris for his coronation as emperor in 1804. Yet newly cut off from state power and dismayed by the Enlightenment’s stress on individualism, Catholic leaders in France, especially, responded to an urbanizing industrial age by erecting what McGreevy calls a “milieu” of schools, seminaries, hospitals, and orphanages as a rigidly ordered parallel world set against unruly civil society. Those “Reform Catholics” (McGreevy’s term) who did strive to fit their local churches into the new order of nation-states met with resistance from the “ultramontanists,” who regarded the pope as a pan-European absolute monarch and the Church as a bulwark against surging democracy.

The conflict came to a head at the First Vatican Council, in 1869. McGreevy cites a French observer’s account of the gathering’s anti-worldly spirit: “The church, through its supreme pastor, says to the lay world, to lay society, and to lay authorities: It is apart from you that I want to exist, to take action, to make decisions, and to develop, affirm, and understand myself.” The ultramontanists prevailed, and the Catholicism then exported to the Americas through mass emigration was leery of democracy—and of citizens’ efforts to expand the right to vote to women and to allow moral issues to be decided by majority rule (or vulgar haggling in the statehouse).

Over time, hostility to modern ideas became the default position of an institution that cleaved to an image of itself as premodern and unchanging. Again and again, the Church’s certainty about what it was against clouded its sense of what it should support, as it adapted to circumstances in ways that seem glaringly inconsistent today. Although the Church criticized the slave trade in Africa, Catholic leaders were slow to support the abolition of slavery in the United States—“so opposed were they to the individualist (at times anti-Catholic) rhetoric they associated with liberal Protestant or secular abolitionists,” McGreevy writes. They fiercely denounced anti-Catholic quotas and discrimination in the United Kingdom, where Anglicanism was the state religion; meanwhile, they ensured that the new republics in Latin America recognized Catholicism as the “national religion,” and often condoned exclusionary practices against Jews and Protestants. Strangely, the Church lined up against both industrial capitalism and working-class socialism—with many Catholics believing that both were controlled by Jews.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 prompted the Church to recognize democracy as a form of government more favorable to belief than atheistic communism was. But the Church’s rejection of Bolshevism led it—in enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend style—to back unjust regimes: Mussolini’s Fascists in Italy, Franco’s Falangists in Spain (where the Loyalists were violently anti-Catholic), and the Nazi Party of Adolf Hitler, whom the Vatican praised for his anti-Bolshevism before adopting its notorious neutrality during World War II. “In majority Catholic states such as Brazil, Portugal, and Austria,” McGreevy observes, politicians and Church leaders together articulated “a distinct Catholic authoritarian vision,” made up of “a fierce anti-communism, an underlying drumbeat of anti-Semitism, and skepticism about democratic politics.”

After the war, the Church boosted Christian Democratic parties in Italy, France, and Germany; endorsed an independence movement led by the Catholic Léopold Senghor in Senegal; backed the Catholic Ngô Ðình Diệm’s postindependence regime in South Vietnam; and propped up antidemocratic oligarchies in Latin America—all as fire walls against communism. It kept up its opposition to postwar stirrings of inclusion—of Catholics in public schools, women in the workplace, sex in the movies.

Yet great ferment was under way in Catholic intellectual life, as theologians at still-robust seminaries in Europe merged Church traditions with continental philosophy. New approaches to liturgy (shifting from Latin to vernacular languages), biblical interpretation (undertaking fresh scrutiny of the Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic sources), and interreligious dialogue (challenging the idea that Catholics were duty-bound to oppose other faiths) thrived. In response, John XXIII called the world’s Catholic bishops to Rome for reflection on the state of the Church in an ecumenical council—Vatican II—and appointed vanguard theologians to advise them.

As the council progressed from 1962 to 1965, the image of Catholicism as a bulwark against modernity was replaced by a vision of a “pilgrim Church” providing humble service to a world in which war, migration, the spread of state-sponsored atheism, and rapid changes in technology had left people desperately in need of a religious perspective. It was time, in McGreevy’s words, “for Catholics and the church to take on the world’s problems as their own,” living their faith (as Pope John had proposed) “in such a way as to attract others less by doctrine than ‘by good example.’ ”

Soon “the world rushed in”: the Cuban missile crisis, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the birth-control pill, the cresting of the movement for Black civil rights. Pope John’s successor, Pope Paul VI, met with Martin Luther King Jr.—over the objections of Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York, who was suspicious of Communist leanings among civil-rights activists. Catholics marched for peace, priests ran for office, and black-clad nuns adopted plain dress and went to graduate school.

The vatican’s opposition to modernity had given Catholics a common adversary to unite against, and had suppressed the Church’s internal disagreements. Vatican II brought these out into the open. Since then, an institution long defined by what it was against has had to ask itself: What is the Church for—what vision of life does it strive to fulfill?

The challenge of offering answers has fallen, at least publicly and rhetorically, to the popes, who have used the papacy to promote distinct programs for engagement with the world. John Paul II affirmed that the Church stands for “a culture of life” against a “culture of death”—taking an approach to human flourishing grounded in a fixed view of gender roles, marriage, and procreation. Benedict XVI saw the Church as the source of objective truth, opposing a “dictatorship of relativism.” Francis proposes that the Church foster “a culture of encounter,” in which people of faith thrive through face-to-face dealings with others of different backgrounds and outlooks, forging a solidarity stronger than nation, class, or ideology.On abortion, the bishops haven’t managed to convince their own people: Polls indicate that Catholics’ views are as varied as those of Americans as a whole.

Vatican II invited Catholics to do openly what they’d tried to do surreptitiously all through the modern age—adapt the Church’s practices to local circumstances where possible—and those papal programs (unfamiliar to most Catholics) have been meant to guide the bishops as they seek to influence civil society in their home countries. Unsurprisingly, consistency has not been the rule since 1965 any more than it was after 1789. Sometimes the tensions involve geopolitics: John Paul championed a people’s movement against oppressive state power in Poland while opposing people’s movements against oppressive state power in Central America. Sometimes they arise from a split between doctrine and practice: Although women now run the offices in many U.S. parishes, the sacramental theology barring women from the priesthood still prevails in Rome. And sometimes a shift in tactics is at work, as when hard-right American Catholics switched from decrying the “activist Court” that ruled in Roe v. Wade to helping form an “activist Court” rooted in traditionalist Catholic principles.

All along, the Church hasn’t been able to shake a habit of opposition to the nation-state when it is seen as running amok. In the U.S., that habit has paradoxically enabled the Church to maintain a robust public profile even as it loses its hold on ordinary believers. Catholic progressives were never so ardent, or so prominent, as when they came together in the 1970s to oppose U.S.-funded authoritarianism in Central and South America. Catholic traditionalists gained cohesion from their unwavering opposition to abortion, a cause that gathered momentum after Roe, aided by the unstinting support of American bishops, who joined fundraising dinners and blessed rallies such as the annual March for Life in Washington. Even as parish life in neighborhoods atrophied and Catholic schools closed, each movement drew headlines, styling itself as a faithful Catholic remnant valiantly standing up to worldly powers. For progressives, the struggle to thwart an anti-communist “Reagan doctrine”—a policy aligned with the Vatican’s—proved exhausting. For traditionalists, by contrast, the striking down of Roe is evidence that a clear message can win out against what they see as ever looser social mores.

The Court’s decision in Dobbs can be seen as a very public victory, too, in the Church’s long and conflict-ridden relations with the state. It’s a victory for the bishops in particular. Only a few years ago, the scandal of clerical sexual abuse—which they and their predecessors had evaded and covered up for decades—seemed to leave them stripped of moral authority. Now they have helped bring about a pronounced legal change on a vexed moral issue.

If it’s a victory, however, it’s a strange one. On abortion, the bishops haven’t managed to convince their own people: Polls indicate that Catholics’ views are as varied as those of Americans as a whole. As men vowed to celibacy, the bishops can’t lead by example on this issue, and for the most part, they haven’t tried coercion—by, say, withholding Communion from pro-abortion-rights Catholics, though that may be changing. Rather, they’ve opted to collaborate with a legal movement that is agnostic on many moral issues (capital punishment, for one, and those involving wealth and poverty), in the interest of elevating a cadre of “originalist” jurists whose rulings have made the anti-abortion position the basis for laws that restrict the rights of Americans broadly.

Strange as the victory is, though, it fits a pattern of Catholic dealings with modernity that will seem familiar from the Church’s history since 1789. The institution has set itself against one aspect of the modern state (an entrenched legal precedent, in this case) by accommodating a different one (the judicial branch, whose structure of appointed potentates resembles the Church hierarchy). The bishops have exercised the power they enjoy as leaders of a large religious community while scanting the views on pregnancy and family of millions of the faithful in that community. Once again, it’s hard to tell what the Catholic Church is for, but everybody knows what it is against.

This article appears in the January/February 2023 print edition.

No comments:

Post a Comment