The Atlantic

When money becomes information, it can inform on you.

APR 8, 2016

TECHNOLOGY

In 2014, Cass Sunstein—one-time “regulatory czar” for the Obama administration—wrote an op-edadvocating for a cashless society, on the grounds that it would reduce street crime. His reasoning? A new study had found an apparent causal relationship between the implementation of the Electronic Benefit Transfer system for welfare benefits, and a drop in crime.

Security, privacy, commerce, and code

Under the new EBT system, welfare recipients could now use debit cards, rather than being forced to cash checks in their entirety—meaning there was less cash circulating in poor neighborhoods. And the less cash there was on the streets, the study’s authors concluded, the less crime there was.

Perhaps burglaries, larcenies, and assaults had gone down because there was simply less to readily steal. Perhaps, also, the debit cards deterred people from spending money on drugs and other black market goods. While nothing was really stopping them from withdrawing cash and then spending it illegally, the famous Sunsteinian Nudge was in effect—the very slightest friction in the environment pushed people away from committing crime.

The year after Sunstein’s op-ed was published, in a seemingly unrelated incident, a student at Columbia University was arrested and charged with five drug-related offenses, including possession with the intent to sell. Supposedly, his fellow students and customers had paid him through the Paypal-owned smartphone app Venmo.

Venmo makes every transaction public by default. The app features a social-network-like feed where you can see your friends sending each other varying sums of money, often accompanied with cute descriptions and emoji. The alleged dealer asked his customers to write a funny description for every transaction, and in doing so, turned his feed (and others’) into an open record of drug trafficking.

Nothing was really stopping the students from going to an ATM and withdrawing cash to use in the old-fashioned way. But that takes time and energy and meanwhile Venmo is sitting right in your pocket. The Ivy League’s best and brightest were Nudged into narcing on themselves.The Ivy League’s best and brightest were Nudged into narcing on themselves.

In a cashless society, the cash has been converted into numbers, into signals, into electronic currents. In short: Information replaces cash.

Information is lightning-quick. It crosses cities, states, and national borders in the twinkle of an eye. It passes through many kinds of devices, flowing from phone to phone, and computer to computer, rather than being sealed away in those silent marble temples we used to call banks. Information never jangles uncomfortably in your pocket.

But wherever information gathers and flows, two predators follow closely behind it: censorship and surveillance. The case of digital money is no exception. Where money becomes a series of signals, it can be censored; where money becomes information, it will inform on you.

* * *

In the spring of 2014, the Department of Justice began to come under fire for Operation Choke Point, an initiativeaimed at discouraging or shutting down exploitative payday lenders. The ends were, on the face of it, benign, but the means were highly dubious.

At the time, the need for consumer protection was painfully obvious, but payday lending was and is still legal. So the DOJ got creative, and askedbanks and payment processors to comply with government policies, and proactively police “high-risk” activity. Banks were asked to voluntarily shut down the kinds of merchant activities that government bureaucrats described as suspicious. The price of resistance was an active investigation by the Department of Justice. By December 2013, the DOJ had issued fifty subpoenas to banks and payment processors.

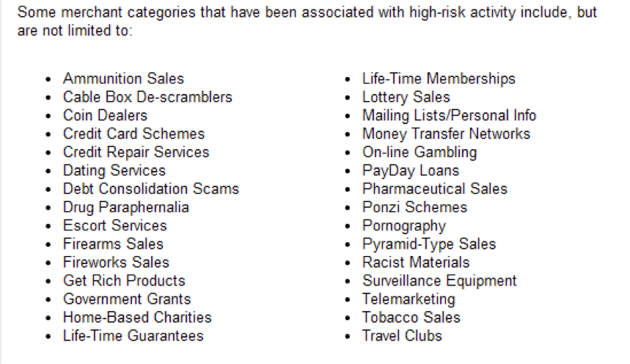

The most vociferous objections to Operation Choke Point came from gun-rights activists, as the firearms and ammunitions industry were labeled “high-risk.” But guns were only one industry among a bizarre miscellany that had been targeted. Tobacco sales, telemarketing, pornography, escort services, dating services, online gambling, coin dealers, cable-box descramblers, and “racist materials” were all explicitly listed on the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) website as “merchant categories that have been associated with high-risk activity.”

Critics of Operation Choke Point saw the initiative as a policing of vice, rather than a consumer protection campaign. Many of the targeted industries—like pornography—could be seen as morally unsavory. And in many cases—as with guns—such moral judgments were highly politicized.One pundit wrote, “[W]hile abortion clinics and environmental groups are probably safe under the Obama administration, if this sort of thing stands, they will be vulnerable to the same tactics if a different administration adopts this same thuggish approach toward the businesses that it dislikes.”

For many conservatives, Operation Choke Point was a new liberal offensive in the culture war, abackhanded attack on the Second Amendment. There was never any evidence that guns were the primary focus of Operation Choke Point, but the outrage continued, fueled by an alarming number of stories of firearms vendors being cut off by credit-card companies or suddenly having their bank accounts closed.

Similarly, porn performers began to report being cut off from the financial system in similar ways, with Chase shutting down the personal bank accounts of “hundreds of adult entertainers” in the spring of 2014. But the troubling effects of Operation Choke Point wouldn’t stop there.

* * *

Eden Alexander fell ill in the spring of 2014. It started when she suffered a severe allergic reaction to a prescribed medication. Then by her account, when she sought medical attention, the care providers declined to treat her, assuming that the problem was illegal drug use.

Alexander is a porn actress. According to her, she was profiled and discriminated against, and failed to receive due medical care. In the end, she developed a staph infection. She couldn’t work, and she struggled to take care of herself, let alone her medical bills, her apartment, her rent, her dogs.

Her friends and supporters—many of whom were also in the adult entertainment industry—started a crowdfunding campaign on the GiveForward platform, hoping to cover her medical expenses. She had raised over a thousand dollars when the campaign was shut down and the payments were frozen.

GiveForward said that her campaign had violated the terms of service of their payment processor, WePay: “WePay’s terms state that you will not accept payments or use the Service in connection with pornographic items.”

A few hours after Alexander received the notice via email, and posted about it on Twitter, she had to be taken to the hospital in an ambulance.At various points in the chain, all transactions squeeze through bottlenecks created by big players like Visa, Mastercard, and Paypal.

The initial reaction on social media was to assume that Alexander had, again, been discriminated against, and that the campaign had been shut down because of the stigma of her occupation. It turned out, however, that one of her supporters had offered to exchange nude pictures for donations to Alexander’s fund, on Twitter. (Of course, this only raises the question of how WePay had discovered the tweet, and whether they were in the habit of policing the Twitter conversations around all of the crowdfunding campaigns they were servicing.)

The suspension of payments to Eden Alexander frustrated her well-wishers and supporters. How could it be so difficult to send Alexander a small amount of money? We live in a world of abundant crowdfunding platforms, and every year brings a fresh crop of money transfer smartphone apps. In the cashless society, payments are supposed to flow more freely and easily than ever.

Of course, the abundance of forward-facing services and apps conceals the infrastructure that made Operation Choke Point possible in the first place. Transactions route through several tangled layers of vendors, processors, and banks. At various points in the chain, all transactions squeeze through bottlenecks created by big players like Visa, Mastercard, and Paypal: These are the choke points for which Operation Choke Point is named.

The choke points are private corporations that are not only subject to government regulation on the books, but have shown a disturbing willingness to bend to extralegal requests—whether it is enforcing financial blockades against the controversial whistleblowing organization WikiLeaks or the website Backpage, which hosts classified ads by sex workers, and allegedly ads from sex traffickers as well. A little bit of pressure, and the whole financial system closes off to the government’s latest pariah. Operation Choke Point exploited this tendency on a wide scale.

It’s probably fair to say that the federal government never targeted Eden Alexander, and that her hospitalization was not a foreseeable consequence of that bare list of bullet points put out by the FDIC—the list that threw “Pornography” next to “Debt Consolidation Scams” and “Get Rich Products.”

FDIC

But subsequent statements made by WePay sketch out a cause-effect relationship between Operation Choke Point and the shutdown of Alexander’s crowdfunding campaigning, revealing how powerful the ripple effects of such initiatives could be. “WePay faces tremendous scrutiny from its partners & card networks around the enforcement of policy, especially when it comes to adult content,” a representative wrote in a blog post. “We must enforce these policies or we face hefty fines or the risk of shutdown for the many hundreds of thousands of merchants on our service. We’re incredibly sorry that these policies added to the difficulties that Eden is facing.”

Where paternalism is bluntly enforced through a bureaucratic game of telephone, unpleasant or even inhumane unintended consequences are bound to result. Looking at the FDIC bullet point list of “high-risk” industries, it’s strange to see a list of a handful of actually-illegal activities (e.g., “scams” and “Ponzi schemes”) alongside legal vices—gambling, tobacco sales, and pornography.

The Electronic Benefit Transfer system is largely benign, and indeed it is a step towards offering banking for the “unbanked”—and that in itself could be a great benefit for a segment of the population that currently must rely on payday loans and check cashing operations. However, it is part of a larger trend, pushing us closer to a world where the cashless society offers the government entirely new forms of coercion, surveillance, and censorship.A cashless society promises a world of limitation, control, and surveillance, which the poorest Americans already have in abundance

EBT nudged society’s most vulnerable closer towards the cashless society; Operation Choke Point used the affordances of the cashless society to enforce what its proponents saw as a consumer protection scheme, and what its critics saw as a campaign against vice. Choke Point rippled out across society—by assessing certain industries as “high-risk,” the FDIC pressured the financial industry into policing and punishing legal activities. Eventually this effect trickled down to WePay, which concluded it had to cut Eden Alexander off from her fundraiser.

Alexander’s ordeal was made possible by our march towards the seemingly inevitable cashless society. Where electronic payments reign supreme, the choke points become more important than ever. Cash has not always been with us—indeed, credit systems predate the use of gold and silver as money. But it is fair to say that we are seeing an unprecedented future in which the totality of financial activity is captured within the same informational system, one that can be both monitored and influenced by a powerful and sprawling administrative state.

The cashless society makes it more possible for the vulnerable to experience Eden Alexander’s ordeal. On the face of it, it’s bizarre that a consumer protection scheme resulted in what Alexander suffered. But consumer protection and anti-vice run along in the same vein: It is all paternalism, and in particular, paternal regulation of the poor.

And when it comes to anti-vice in particular, the poor suffer the most—they are held to a higher moral standard than others, and are policed and punished for straying from it. Welfare recipients must undergo invasive and time-consuming drug testing. Women (often women of color) walking in areas “known for prostitution” are hassled or even arrested for simply carrying condoms in their purse.

A cashless society promises a world of limitation, control, and surveillance—all of which the poorest Americans already have in abundance, of course. For the most vulnerable, the cashless society offers nothing substantively new, it only extends the reach of the existing paternal bureaucratic state.

* * *

The poor may be disparately impacted, but the cashless society affects everyone. And so relatively privileged technolibertarians have long feared the cashless society, seeing it as an electronic Panopticon, one of a host of privacy erosions introduced by the digital age. This fear has motivated a number of innovations, from David Chaum’s ecash (described in his 1985 paper “Security without identification: transaction systems to make big brother obsolete”), to the much-hyped Bitcoin protocol.Cryptocurrency isn’t really a federal priority, and as long as that’s the case, it can be a viable backchannel when payment processors institute blockades.

Chaum focused on circumventing the surveillance-capabilities of digital cash; bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator (or creators) Satoshi Nakamoto focused on eliminating the ability of trusted third parties to prevent or reverse transactions—the very capability that allows the kind of financial censorship encouraged by Operation Choke Point. These cryptocurrencies are attempts to create vents and pockets of freedom inside the future cashless world.

Their success has been, at best, dubious. I needn’t tell you about the viability of ecash. If you’ve heard of it, you already know; if you haven’t, that tells you everything already. As for bitcoin, while it has certainly seen greater adoption, the digital currency has been hit with increasing regulation, concentrated on the bitcoin exchanges which trade government currency for bitcoin. This regulatory trend has recreated the very same bottlenecks and choke points that Satoshi Nakamoto sought to circumvent in the first place.

But cryptocurrency isn’t really a federal priority, and as long as that’s the case, it can be a viable backchannel when payment processors institute blockades. Payment processors stopped serving WikiLeaks in the wake of Cablegate; eventually the organization was funded mostly through bitcoin. And when Visa and Mastercard stopped serving Backpage in 2015, sex workers also turned to bitcoin.

* * *

In June 2015, Thomas Dart, the sheriff of Cook County—the largest county in Illinois, which includes the city of Chicago—wrote an open letter to the major payment processors. “As the Sheriff of Cook County, a father and a caring citizen, I write to request that your institution immediately cease and desist from allowing your credit cards to be used to place ads on websites like Backpage.com.”

Backpage is a website that hosts classified ads, including ads from escorts. It is so prominent it has been called “America’s largest escort site.” According to several anti-sex-trafficking organizations, it is also a haven for sexual slavery. Some sex workers say, however, that if they themselves are prevented from advertising, they are put in harm’s way. “[H]aving the ability to advertise online allows sex workers to more carefully screen potential customers and work indoors,” writes Alison Bass. “Research shows that when sex workers can’t advertise online and screen clients, they are often forced onto the street, where it is more difficult to screen out violent clients and negotiate safe sex (i.e. sex with condoms). They are also more likely to have to depend on exploitative pimps to find customers for them.”

The nuances of this debate were never argued in a legislature or even a court of law. Visa and Mastercard immediately folded in the face of Dart’s letter, and stopped serving Backpage, making it nearly impossible for sex workers (and allegedly traffickers as well) to advertise.Financial censorship could become pervasive, unbarred by any meaningful legal rights or guarantees.

Dart’s open letter resembled Operation Choke Point, in a far flimsier yet more menacing fashion. If Dart had brought a legal action against Backpage, he would have no doubt been trounced in court. The sheriff had already lost a lawsuit against Craigslist in 2009 over their erotic services ads. Although Dart clearly identified himself as the Sheriff of Cook County, he never actually said he was actually going to enforce any law against Visa, Mastercard, or even Backpage. The letter made reference to the federal anti-money-laundering statute and to the alleged existence of sex-trafficking on the website, but it was in essence a missive composed to elicit fear, uncertainty, and doubt. As with Operation Choke Point, it was a request for voluntary action, rather than a criminal complaint, indictment, or injunction.

Perhaps if Visa or Mastercard had put up a fight, Dart would have followed through on his veiled threats, the way the Department of Justice issued subpoenas to errant banks and processors. But because the two companies capitulated instantly, there’s no way of knowing.

In December 2015, a federal appeals court in Illinois granted Backpage an injunction against Dart. The opinion, written by the esteemed Richard Posner, ripped into Dart for trying to “shut down an avenue of expression of ideas and opinions through ‘actual or threatened imposition of government power or sanction’” in violation of the First Amendment.

In court, Visa claimed that “at no point did Visa perceive Sheriff Dart to be threatening Visa,” and that it had simply made a voluntary choice to stop servicing Backpage. But back in June, Dart’s director of communications had sent an email informing Visa that the Sheriff’s office was about to hold a press conference on Backpage and sex trafficking, and that “[o]bviously the tone of the press conference will change considerably if your executives see fit to sever ties with Backpage and its imitators.” Internal emails between Visa employees at the time referred to the Dart press conference email as “blackmail.”

For Judge Posner, Dart’s tactics were troubling. They could be easily replicated, following a formula of “unauthorized, unregulated, foolproof, lawless government coercion ... coupling threats with denunciations of the activity that the official wants stamped out, for the target of the denunciation will be reluctant to acknowledge that he is submitting to threats but will instead ascribe his abandonment of the activity to his having discovered that it offends his moral principles.”

Posner made no mention of it in his opinion, but the same strategy had been repeated years earlier, when Senator Joseph Lieberman had convinced the payment processors to cut off WikiLeaks in the wake of the publication of the State Department diplomatic cables. As with Backpage, and was with Operation Chokepoint, this was a “voluntary” decision on their part. The financial blockade would only be lifted (partially) two years later in 2013.

The Seventh Circuit Backpage decision is an important First Amendment precedent, a much-needed corrective in an age of ever-more-frequent financial blockading. But much of the decision builds its case by pointing to Sherriff Dart’s hamfisted tactics, the obvious coercion that Visa employees called “blackmail” in writing. What happens to a more factually subtle case that lands in front of a less-libertarian-leaning judge?

As paper money evaporates from our pockets and the whole country—even world—becomes enveloped by the cashless society, financial censorship could become pervasive, unbarred by any meaningful legal rights or guarantees.

* * *

In January 2011, shortly after the WikiLeaks financial blockade was put into place, the founder of WePay posted an Ask Me Anything on Reddit, calling his company the “anti-Paypal.” He wrote that he was particularly concerned with how readily PayPal froze accounts that collected money for good causes.

It had only been a month or two since payment processors—including PayPal—had chosen to blockade WikiLeaks. So predictably, one commenter asked a direct question about WikiLeaks.

“Theoretically, you can use WePay to collect money from people in your social circles, and donate that money to whomever you'd like,” he wrote in response. “That being said, we've intentionally tried to keep our heads down and sit on the sidelines for this one. … [W]e pride ourselves on not freezing accounts, but in extreme cases like wikileaks, there is always the chance that authorities will force us to do so.”

Four years later, the company seemed to have decided that a fundraiser for a sex worker’s hospital bills was an extreme case like WikiLeaks.

But subsequent statements made by WePay sketch out a cause-effect relationship between Operation Choke Point and the shutdown of Alexander’s crowdfunding campaigning, revealing how powerful the ripple effects of such initiatives could be. “WePay faces tremendous scrutiny from its partners & card networks around the enforcement of policy, especially when it comes to adult content,” a representative wrote in a blog post. “We must enforce these policies or we face hefty fines or the risk of shutdown for the many hundreds of thousands of merchants on our service. We’re incredibly sorry that these policies added to the difficulties that Eden is facing.”

Where paternalism is bluntly enforced through a bureaucratic game of telephone, unpleasant or even inhumane unintended consequences are bound to result. Looking at the FDIC bullet point list of “high-risk” industries, it’s strange to see a list of a handful of actually-illegal activities (e.g., “scams” and “Ponzi schemes”) alongside legal vices—gambling, tobacco sales, and pornography.

The Electronic Benefit Transfer system is largely benign, and indeed it is a step towards offering banking for the “unbanked”—and that in itself could be a great benefit for a segment of the population that currently must rely on payday loans and check cashing operations. However, it is part of a larger trend, pushing us closer to a world where the cashless society offers the government entirely new forms of coercion, surveillance, and censorship.A cashless society promises a world of limitation, control, and surveillance, which the poorest Americans already have in abundance

EBT nudged society’s most vulnerable closer towards the cashless society; Operation Choke Point used the affordances of the cashless society to enforce what its proponents saw as a consumer protection scheme, and what its critics saw as a campaign against vice. Choke Point rippled out across society—by assessing certain industries as “high-risk,” the FDIC pressured the financial industry into policing and punishing legal activities. Eventually this effect trickled down to WePay, which concluded it had to cut Eden Alexander off from her fundraiser.

Alexander’s ordeal was made possible by our march towards the seemingly inevitable cashless society. Where electronic payments reign supreme, the choke points become more important than ever. Cash has not always been with us—indeed, credit systems predate the use of gold and silver as money. But it is fair to say that we are seeing an unprecedented future in which the totality of financial activity is captured within the same informational system, one that can be both monitored and influenced by a powerful and sprawling administrative state.

The cashless society makes it more possible for the vulnerable to experience Eden Alexander’s ordeal. On the face of it, it’s bizarre that a consumer protection scheme resulted in what Alexander suffered. But consumer protection and anti-vice run along in the same vein: It is all paternalism, and in particular, paternal regulation of the poor.

And when it comes to anti-vice in particular, the poor suffer the most—they are held to a higher moral standard than others, and are policed and punished for straying from it. Welfare recipients must undergo invasive and time-consuming drug testing. Women (often women of color) walking in areas “known for prostitution” are hassled or even arrested for simply carrying condoms in their purse.

A cashless society promises a world of limitation, control, and surveillance—all of which the poorest Americans already have in abundance, of course. For the most vulnerable, the cashless society offers nothing substantively new, it only extends the reach of the existing paternal bureaucratic state.

* * *

The poor may be disparately impacted, but the cashless society affects everyone. And so relatively privileged technolibertarians have long feared the cashless society, seeing it as an electronic Panopticon, one of a host of privacy erosions introduced by the digital age. This fear has motivated a number of innovations, from David Chaum’s ecash (described in his 1985 paper “Security without identification: transaction systems to make big brother obsolete”), to the much-hyped Bitcoin protocol.Cryptocurrency isn’t really a federal priority, and as long as that’s the case, it can be a viable backchannel when payment processors institute blockades.

Chaum focused on circumventing the surveillance-capabilities of digital cash; bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator (or creators) Satoshi Nakamoto focused on eliminating the ability of trusted third parties to prevent or reverse transactions—the very capability that allows the kind of financial censorship encouraged by Operation Choke Point. These cryptocurrencies are attempts to create vents and pockets of freedom inside the future cashless world.

Their success has been, at best, dubious. I needn’t tell you about the viability of ecash. If you’ve heard of it, you already know; if you haven’t, that tells you everything already. As for bitcoin, while it has certainly seen greater adoption, the digital currency has been hit with increasing regulation, concentrated on the bitcoin exchanges which trade government currency for bitcoin. This regulatory trend has recreated the very same bottlenecks and choke points that Satoshi Nakamoto sought to circumvent in the first place.

But cryptocurrency isn’t really a federal priority, and as long as that’s the case, it can be a viable backchannel when payment processors institute blockades. Payment processors stopped serving WikiLeaks in the wake of Cablegate; eventually the organization was funded mostly through bitcoin. And when Visa and Mastercard stopped serving Backpage in 2015, sex workers also turned to bitcoin.

* * *

In June 2015, Thomas Dart, the sheriff of Cook County—the largest county in Illinois, which includes the city of Chicago—wrote an open letter to the major payment processors. “As the Sheriff of Cook County, a father and a caring citizen, I write to request that your institution immediately cease and desist from allowing your credit cards to be used to place ads on websites like Backpage.com.”

Backpage is a website that hosts classified ads, including ads from escorts. It is so prominent it has been called “America’s largest escort site.” According to several anti-sex-trafficking organizations, it is also a haven for sexual slavery. Some sex workers say, however, that if they themselves are prevented from advertising, they are put in harm’s way. “[H]aving the ability to advertise online allows sex workers to more carefully screen potential customers and work indoors,” writes Alison Bass. “Research shows that when sex workers can’t advertise online and screen clients, they are often forced onto the street, where it is more difficult to screen out violent clients and negotiate safe sex (i.e. sex with condoms). They are also more likely to have to depend on exploitative pimps to find customers for them.”

The nuances of this debate were never argued in a legislature or even a court of law. Visa and Mastercard immediately folded in the face of Dart’s letter, and stopped serving Backpage, making it nearly impossible for sex workers (and allegedly traffickers as well) to advertise.Financial censorship could become pervasive, unbarred by any meaningful legal rights or guarantees.

Dart’s open letter resembled Operation Choke Point, in a far flimsier yet more menacing fashion. If Dart had brought a legal action against Backpage, he would have no doubt been trounced in court. The sheriff had already lost a lawsuit against Craigslist in 2009 over their erotic services ads. Although Dart clearly identified himself as the Sheriff of Cook County, he never actually said he was actually going to enforce any law against Visa, Mastercard, or even Backpage. The letter made reference to the federal anti-money-laundering statute and to the alleged existence of sex-trafficking on the website, but it was in essence a missive composed to elicit fear, uncertainty, and doubt. As with Operation Choke Point, it was a request for voluntary action, rather than a criminal complaint, indictment, or injunction.

Perhaps if Visa or Mastercard had put up a fight, Dart would have followed through on his veiled threats, the way the Department of Justice issued subpoenas to errant banks and processors. But because the two companies capitulated instantly, there’s no way of knowing.

In December 2015, a federal appeals court in Illinois granted Backpage an injunction against Dart. The opinion, written by the esteemed Richard Posner, ripped into Dart for trying to “shut down an avenue of expression of ideas and opinions through ‘actual or threatened imposition of government power or sanction’” in violation of the First Amendment.

In court, Visa claimed that “at no point did Visa perceive Sheriff Dart to be threatening Visa,” and that it had simply made a voluntary choice to stop servicing Backpage. But back in June, Dart’s director of communications had sent an email informing Visa that the Sheriff’s office was about to hold a press conference on Backpage and sex trafficking, and that “[o]bviously the tone of the press conference will change considerably if your executives see fit to sever ties with Backpage and its imitators.” Internal emails between Visa employees at the time referred to the Dart press conference email as “blackmail.”

For Judge Posner, Dart’s tactics were troubling. They could be easily replicated, following a formula of “unauthorized, unregulated, foolproof, lawless government coercion ... coupling threats with denunciations of the activity that the official wants stamped out, for the target of the denunciation will be reluctant to acknowledge that he is submitting to threats but will instead ascribe his abandonment of the activity to his having discovered that it offends his moral principles.”

Posner made no mention of it in his opinion, but the same strategy had been repeated years earlier, when Senator Joseph Lieberman had convinced the payment processors to cut off WikiLeaks in the wake of the publication of the State Department diplomatic cables. As with Backpage, and was with Operation Chokepoint, this was a “voluntary” decision on their part. The financial blockade would only be lifted (partially) two years later in 2013.

The Seventh Circuit Backpage decision is an important First Amendment precedent, a much-needed corrective in an age of ever-more-frequent financial blockading. But much of the decision builds its case by pointing to Sherriff Dart’s hamfisted tactics, the obvious coercion that Visa employees called “blackmail” in writing. What happens to a more factually subtle case that lands in front of a less-libertarian-leaning judge?

As paper money evaporates from our pockets and the whole country—even world—becomes enveloped by the cashless society, financial censorship could become pervasive, unbarred by any meaningful legal rights or guarantees.

* * *

In January 2011, shortly after the WikiLeaks financial blockade was put into place, the founder of WePay posted an Ask Me Anything on Reddit, calling his company the “anti-Paypal.” He wrote that he was particularly concerned with how readily PayPal froze accounts that collected money for good causes.

It had only been a month or two since payment processors—including PayPal—had chosen to blockade WikiLeaks. So predictably, one commenter asked a direct question about WikiLeaks.

“Theoretically, you can use WePay to collect money from people in your social circles, and donate that money to whomever you'd like,” he wrote in response. “That being said, we've intentionally tried to keep our heads down and sit on the sidelines for this one. … [W]e pride ourselves on not freezing accounts, but in extreme cases like wikileaks, there is always the chance that authorities will force us to do so.”

Four years later, the company seemed to have decided that a fundraiser for a sex worker’s hospital bills was an extreme case like WikiLeaks.

No comments:

Post a Comment