Behind the schoolgirl climate warrior lies a shadowy cabal of lobbyists, investors and energy companies seeking to profit from a green bonanza

30/05/2019

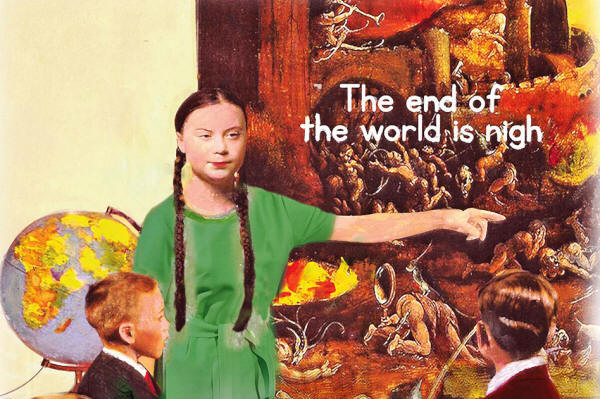

(ILLUSTRATION BY MIRIAM ELIA)

Greta Thunberg is just an ordinary 16-year-old Swedish schoolgirl whose fiery visions have convinced the parliaments of Britain and Ireland to declare a “climate emergency”. Greta’s parents, actor Svante Thunberg and opera singer Malena Ernman, are just an ordinary pair of parent-managers who want to save the planet. Query their motives, and you risk being accused of “climate denial”, or of bullying a vulnerable child with Asperger’s. But the Greta phenomenon has also involved green lobbyists, PR hustlers, eco-academics, and a think-tank founded by a wealthy ex-minister in Sweden’s Social Democratic government with links to the country’s energy companies. These companies are preparing for the biggest bonanza of government contracts in history: the greening of the Western economies. Greta, whether she and her parents know it or not, is the face of their political strategy.

The family’s story is that Greta launched a one-girl “school strike” at the Swedish parliament on the morning of August 20, 2018. Ingmar Rentzhog, founder of the social media platform We Have No Time, happened to be passing. Inspired, Rentzhog posted Greta’s photograph on his personal Facebook page. By late afternoon, the newspaper Dagens Nyheter had Greta’s story and face on its website. The rest is viral.

But this isn’t the full story. In emails, media entrepeneur Rentzhog told me that he “met Greta for the first time” at the parliament, and that he “did not know Greta or Greta’s parents” before then. Yet in the same emails, Rentzhog admitted to meeting Greta’s mother Malena Ernman “3-4 months before everything started”—in early May 2018, when he and Malena had shared a stage at a conference called the Climate Parliament. Nor did Rentzhog stumble on Greta’s protest by accident. He now admits to having been informed “the week before” by “a mailing list from a climate activist” named Bo Thorén, leader of the Fossil Free Dalsland group.

Independent journalist Rebecca Weidmo Uvell has obtained an earlier email from Bo Thorén’s search for fresh green faces. In February 2018, Thorén invited a group of environmental activists, academics and politicians to plan “how we can involve and get help from young people to increase the pace of the transition to a sustainable society”. In May, after Greta won second prize in an environmental op-ed writing competition run by the newspaper Svenska Dagbladet, Thorén approached all the competition winners with a plan for a “school strike”, modelled on the student walk-outs after the shootings at Parkland, Florida. “But no one was interested,” Greta’s mother claims, “so Greta decided to do it for herself.”

Fortunately, Greta’s decision coincided with the publication of Scenes from the Heart, Svante and Malena’s memoir of how saving the planet had saved their family. Unfortunately, Malena omitted to tell her publisher that Ingmar Rentzhog had commandeered Greta’s stunt.

“We had a problem,” says Malena’s editor, Jonas Axelsson. “Journalists asked if it was promotion for the book. It wasn’t at all. It was a nightmare.”

It was, however, a dream for Ingmar Rentzhog. When Rentzhog combined Thorén’s plan and Malena Ernman’s musical fame with Greta’s uncanny charisma and We Have No Time’s mailing list, he turned Greta into a viral celebrity.

“I have not invented Greta,” Rentzhog insists, “but I helped to spread her action to an international audience.”

Trained by Al Gore’s Climate Reality Project, Rentzhog set up We Don’t Have Time in late 2017 to “hold leaders and companies accountable for climate change” by leveraging “the power of social media”. Rentzhog and his CEO David Olsson have backgrounds in finance, not environmental activism, Rentzhog as the founder of Laika, an investment relations company, and Olsson with Svenska Bostadsfonden, one of Sweden’s biggest real estate funds, whose board Rentzhog joined in June 2017. We Don’t Have Time’s investors included Gustav Stenbeck, whose family control Kinnevik, one of Sweden’s largest investment corporations.

In May 2018, Rentzhog and Olsson of We Don’t Have Time became chairman and board member of a think-tank called Global Utmaning (Global Challenge). Its founder, Kristina Persson, is an heir to an industrial fortune. She is a career trade unionist and a Social Democrat politician going back to the party’s golden age under Olof Palme. She is also an ex-deputy governor of Sweden’s central bank and a New Ager who has discussed her reincarnations and communication with the dead. Between 2014 and 2016, Persson served as “Minister for the Future” in the Social Democratic government of Stefan Lofven.

Petter Skogar, president of Sweden’s biggest employer’s association, is on Global Challenge’s ten-person board. So is Johan Lindholm, chairman of the Union of Construction Workers and member of the Social Democrats’ executive board. So is Anders Wijkman, president of the Club of Rome, chair of the Environmental Objectives Council, and a recipient in February 2018 of Bo Thorén’s call for youth mobilisation. So is Catherina Nystedt Ringborg, former CEO of Swedish Water, advisor at the International Energy Agency, and former vice-president at Swedish-Swiss energy giant ABB.

Catherina Ringborg is also a member of green energy venture capital firm Sustainable Energy Angels. Its members are a who’s who of the Swedish energy sector. Sustainable Energy Angels’ president and chair of investment committee are ex-ABB personnel, and so are four of its 17 members.

When Greta met Rentzhog, he was the salaried chairman of a private think-tank owned by an ex-Social Democrat minister with a background in the energy sector. His board was stacked with powerful sectoral interests, including career Social Democrats, major union leaders, and lobbyists with links to Brussels. And his board’s vice-chair was a member of one of Sweden’s most powerful green energy investment groups.

Greta and her parents probably did not know this. Rentzhog seems to have wanted to keep it that way. On September 2, 2018, a week after Rentzhog claimed to have stumbled on Greta, Dagens Nyheter ran a long op-ed on the need to force the greening of the global economy by “bottom-up” action against national governments, including “broad social mobilisation . . . reminiscent of what takes place in communities threatened by war”. Greta’s mother was one of the nine signatories. Ex-Minister for the Future Kristina Persson and three other Global Challenge board members signed the op-ed but cited other affiliations. Only Rentzhog admitted that he was associated with Global Challenge.

An English edition of the article identifies Rentzhog and Wijkman as its authors. Rentzhog claims that “many of us involved in Global Challenge were also involved” in writing it. He admits that he showed Malena Ernman “the article and the other signatures, but not their titles for Global Challenge”.

Greta’s father Svante, who now devotes himself to managing her career, declined my interview requests and refused to reply to a detailed list of written questions about Ingmar Rentzhog and Global Challenge. Instead, Svante issued an evasive three-paragraph statement through an intermediary. He says that “neither I nor Greta feel qualified to answer” questions about Rentzhog’s business connections, and when the family might have known about them. Svante also claims that “we have never worked with” We Have No Time or Global Challenge. Yet Greta served on We Have No Time’s advisory board between November 2018 and January 2019, and Malena Ernman signed a letter with four Global Challenge board members.

When I asked Rentzhog if he had introduced Greta and her parents to other Global Challenge board members, he replied, “I don’t know, maybe I did, but if Svante says no, maybe it was not connected.” Svante refuses to answer my questions about whether he and Greta have met members of the Global Challenge board. But Global Challenge board member Anders Wijkman remembers.

Wijkman leads the anti-growth Club of Rome. Its alarmist 1972 report, A Limit to Growth?, has become a cornerstone of the “climate emergency” campaign. In December 2018, We Have No Time and Global Challenge launched the Club of Rome’s latest vision of apocalypse, the Climate Emergency Plan. Greta, Rentzhog told me, was invited to the launch event, but was unable to attend as she was already booked to deliver a TED Talk.

The Climate Emergency Plan’s talking points are Greta’s talking points. “Around the year 2030, in ten years, 250 days, and ten hours,” the Scandinavian Cassandra told British parliamentarians, “we will be in a position where we set off an irreversible chain reaction beyond human control that will most likely lead to the end of our civilisation as we know it.” The only way to save ourselves is to follow the Climate Emergency Plan, and instantly green the global energy business through massive government investment and emergency legislation. Wijkman of the Club of Rome sees Greta as vital to pushing the “climate emergency” strategy on Europe’s political class.

“We had many scientist and climate researchers who’ve been speaking in terms of emergency for a number of years,” he told me, “but it’s only now, in the last couple of months, that the concept of emergency has been more or less accepted.”

Greta, Wijkman says, has been “instrumental” to this breakthrough. “Young people seemed not to pay much attention only half a year ago, but now obviously they do. So she has been a lightning rod or catalyst of this.”

Has Ingmar Rentzhog been essential to Greta’s rise?

“Yes, yes,” Wijkman agrees, though he finds it hard to quantify. “I don’t know how much he’s been influential. I think that Greta and her father and mother are quite skilled.”

Greta’s father Svante claims she “acts independently of any organisation or individual”. But Wijkman says Greta has “good advisers”, such as climate change professor Kevin Anderson. Anderson claims only to “discuss” Greta’s ideas and “correct” her manuscripts.“I know that he has given her a lot of advice in terms of substance,” Wijkman says.

In January, Rentzhog and We Have No Time used Greta’s face and story in promotional materials for a share issue for a new venture. Rentzhog claimed that the family knew, but Greta and her parents parents insisted that they did not. They announced that their association with Rentzhog was over—a curious statement, considering that Svante claims they had never associated with him in the first place. Greta’s new press agent, Daniel Donner, works from the office of a Brussels lobby group, the European Climate Foundation. Still, We Don’t Have Time retweet Greta as if nothing has changed. In a way, nothing has.

Whatever Greta or her parents know or think, her eco-mob increases the likelihood of legislation and investment that will make colossal profits for people like Global Challenge, We Don’t Have Time and Sustainable Energy Angels. For Sweden’s energy titans, saving the planet means government contracts to print the green stuff. Green energy lobbyists use populist scare tactics and a children’s crusade to bypass elected representatives, but their goal is technocracy not democracy, profit not redistribution. Greta, a child of woke capitalism, is being used to ease the transition to green corporatism.

No comments:

Post a Comment