October 18, 2017

What Catholics in post-Protestant democracy can learn from medieval monarchs

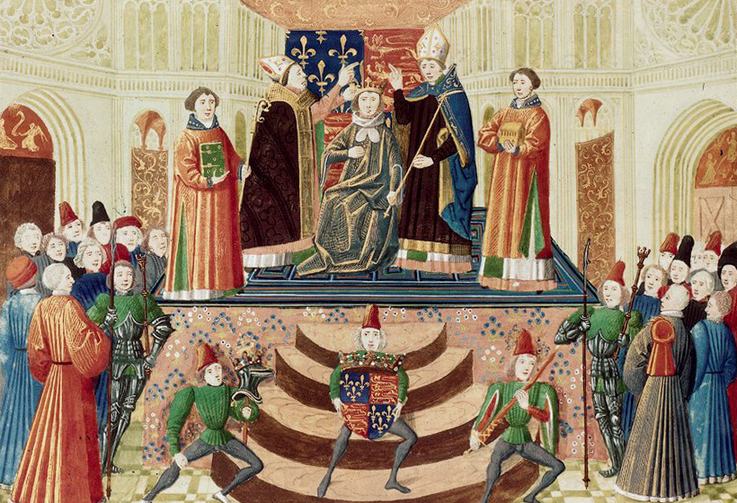

Coronation of Henry IV at Westminster in 1399

One thing is certain: The proper role of religion in civil life is not a new question. It was already raised with Jesus, and we hear his answer, which begs another question: Why do we keep debating the issue?

One of this year’s most widely read books, on this very topic, is Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation. His scheme is easily summarized: There is no longer a place for Christians or our ideas in American civil life so we had best enter self-constructed, protective ghettos, as we ride out the collapse of this civilization.

One thing is sure: The proper role of religion in civil life is not a new question.

Perhaps the other extreme is best illustrated by a Fox News commentator, who this past week called the U.S. Constitution “the most sublime document ever authored.” If Mr. Dreher thinks Christians must go their own way, this commentator virtually identified the American way with God’s will. Evidently for him, even the Gospels fall in place behind the Constitution.

Whether it is a middle way or simply the right way, something can be learned by Christians, even by American Christians, from the medieval—and hence Catholic—coronation oath of English sovereigns, which did not differ all that much from the oaths taken by other Catholic sovereigns. (If the European Union collapses through the exertion of protesting partisans, it will do so for the second time. The first union was called Christendom.)

What can a post-Protestant democracy possibly learn from the Catholic coronation oath of English sovereigns?

Tweet this

I know what you are thinking: You have got to be kidding. What can a post-Protestant democracy possibly learn from such a source?

But let’s take a look. The monarch, who was about to assume personal responsibility for the state, was asked to affirm the following:

Sir, will you grant and keep, and by your oath confirm, to the people of England, the laws and customs to them granted, by the kings of England your lawful and religious predecessors; and namely the laws customs and franchises granted to the clergy by the glorious King St. Edward your predecessor according to the laws of God, the true profession of the gospel established in the Church of England, and agreeable to the prerogative of the King thereof, and the ancient customs of this realm?

I grant and promise to keep them.

Sir, will you keep peace and godly agreement, entirely according to your power, both to God, the holy Church, the clergy, the people?

I will keep it.

Sir, will you to your power cause law, justice and discretion, in mercy and truth, to be executed in all your judgements?

I will.

Will you grant to hold and keep, the laws and rightful customs, which the commalty of this your kingdom have; and will you defend, and uphold them to the honour of God, so much as in you lieth:

I grant and promise so to do.

What can Christians in a—yes, quite possibly—post-Christian democracy learn from this oath?

First, if we the people are ourselves responsible for the good of the state, then we have the same obligations that a medieval monarch once had. We have an obligation, each one of us, before God, to look after the well-being of all people: the “peace and godly agreement” of the oath. We and everyone else in the world receive all that we have and are from God, which, translated into secular speak means we have no more right to power than any other person. All people exist to serve all other people. Mutual respect for each other does not come from our political agreements. On the contrary, it is the source of any possible agreement.

If we the people are ourselves responsible for the good of the state, then we have the same obligations that a medieval monarch once had.

Second, we can only serve the well-being of people by searching for truth—and not just truth in the abstract but a truth that brings well-being to all people: the “law, justice and discretion, in mercy and truth” of the medieval oath. This is a practical, political truth that can only be discovered by dialogue with each other. Politics may be the nastiest work on earth but, before God, it is also the noblest. It never ceases to search for the well-being of all people. None, especially Christians, can abstain from this quest. As believers, we profess that there is such a thing as truth, something that transcends the small claims of all partisans.

God is the word we believers use to reject all human idols.

Third, today, those who are religious make an essential contribution to our common life, one bound up in our profession of belief in God. To say, “I believe in God” is not to posit some invisible sovereign in the sky. It is to say that anything that stops the search for truth and the well-being it brings is idolatrous. God is not our agenda. Our agenda aims at God—the “honour of God” in the oath—a God we do not as yet possess or comprehend, save in mystery. God is the word we believers use to reject all human idols, which stunt our growth in grace, those fashioned by the religious and the irreligious.

Fourth and finally, none of us can impose our will upon the world because the world is bigger than any individual or collective. Each person, each community, each nation must see to the particular in service of the universal. Like the medieval monarch, we must faithfully attend to “the laws and customs” bequeathed to us by previous generations of seekers, altering them only according to the demands of unfolding truth. If, in the particular, we seek the truth that fosters well-being, then the well-being of the universal will come to fruition as a gift of God, for those who believe or as the sacrifice of self for those who, as yet, know nothing of what it means to believe.

Readings: Isaiah 45:1, 4-6 1 Thessalonians 1:1-5b Matthew 21:15-22

Source: https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/10/18/what-catholics-post-protestant-democracy-can-learn-medieval-monarchs

No comments:

Post a Comment