Jan 13 2018, 2:16 pm ET

by James Rainey

The threats seem to come almost daily now out of North Korea — ballistic missile firings, preparations to test a nuclear bomb and routine bravado. In April, state-owned media in the rogue nation vowed a “super mighty preemptive strike,” one that will reduce the U.S. to “ashes.”

On Saturday, residents in Hawaii were sent into a panic when they received alerts on their mobile phones and televisions warning that a ballistic missile was on its way. The warning, which claimed "this is not a drill," quickly prompted officials to say minutes later that it was sent in error.

Meanwhile, American weapons experts believe Pyongyang is likely a few years from having the capability of firing a nuclear–equipped missile that can reach the U.S. mainland.

Yet some leading emergency response planners view the persistent menace of North Korea as a new opportunity: reason to alert the American public that a limited nuclear attack can be survivable, with a few precautions.

North Korea Threat Growing or Just Saber-Rattling?

The simplest of the warnings is: "Don’t run. Get inside." Sheltering in place, beneath as many layers of protection as possible, is the best way to avoid the radiation that would follow a nuclear detonation.

That conclusion has been the consensus of the U.S. emergency and public health establishments for years, though national, state and local governments generally have been less than aggressive about putting the word out to the public. “The goal is to put as many walls and as much concrete, brick and soil between you and the radioactive material outside.”

Officials at the Federal Emergency Management Agency and Department of Homeland Security say the nuclear safety directives are available, including online at Ready.gov, but they have not broadcast them more widely. Asked about spreading the word beyond the website, a FEMA spokesperson emailed a terse response: "At this time time there are no specific plans to do any messaging on this topic."

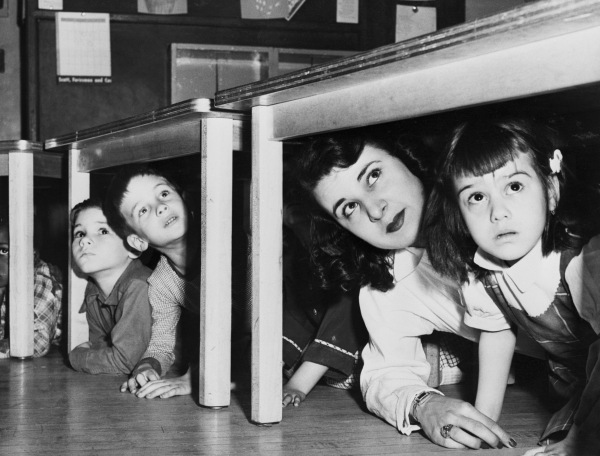

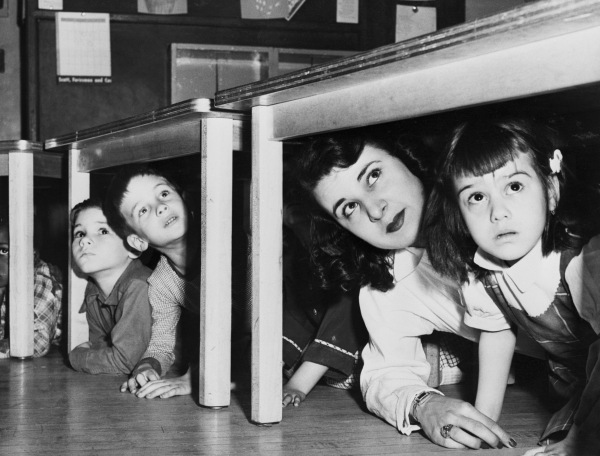

School children and their teacher peer from beneath a table during a state-wide air raid test in Newark, New Jersey, in 1952. Bettmann / Getty Images

Part of the reticence has been out of a fear of alarming the public and part has been an attempt to balance education about “radiation safety” with other messages about threats like earthquakes, hurricanes and floods, say academics who advise the government.

“There is a lot of fatalism on this subject, the feeling that there will be untold death and destruction and there is nothing to be done,” said Irwin Redlener, director of Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness. “But the thing that is frustrating for me is that, with some very simple public messaging, we could save hundreds of thousands of lives in a nuclear detonation.”

Duck-and-cover drills a thing of the past

Brooke Buddemeier, a nationally-recognized expert on nuclear disaster preparedness from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, said that following the 9/11 attacks, Americans may have suffered a kind of “preparedness fatigue.”

“There was so much information that came out altogether,” Buddemeier said, “but then it’s kind of hard to fit information about nuclear terrorism in with warnings about earthquakes and hurricanes and wildfires and all other emergencies that happen on a regular basis.”

The last time that the threat of imminent nuclear attack gripped the American conscious, John F. Kennedy was in the White House. But duck-and-cover drills soon became a thing of the past and at-home fallout shelters are a rarity.

Local governments abandoned the mass public shelters they built during the Cold War. Parking garages beneath the Los Angeles Civic Center and a subterranean vault beneath a Seattle freeway overpass are no longer designated as safe zones for a retreating public.

While North Korean provocations have received the most attention in recent weeks, government officials remain at least as concerned about the possibility of an attack by terrorists or other “non-state” actors. In these scenarios, a nuclear device might be secreted into a ship, or some other delivery device, and exploded at ground level.

The largest nuclear blasts would create a fireball a mile in diameter and temperatures as hot as the surface of the sun, followed quickly by winds greater than the force of a hurricane, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. (North Korea’s past nuclear tests have been far smaller, with the largest an estimated 10 kilotons, less than either of the atomic bombs used on Japan in World War II). Radioactive fallout would be carried for miles by the jet stream and surface winds. While little might be done for immediate blast victims, researchers say that the public’s response will be crucial.

Trump to U.N. Security Council Diplomats: Remove 'Blindfolds' on North Korea

Resist the instinct to run for the hills

Years of novels, television and movie dramatizations have popularized visions of nuke victims flowing out of cities in unruly masses, seeking out radiation-free air. But experts say that finding a route to safety would range from difficult to impossible, given the droves who would be gridlocking freeways.

Survivors of an immediate blast would be much better served by finding cover. A car is better than the open air, while most houses are considerably safer than a car, particularly if there is room to hunker down in a basement.

“Go as far below ground as possible or in the center of a tall building,” says Ready.gov, the website created by FEMA and the Department of Homeland Security. “The goal is to put as many walls and as much concrete, brick and soil between you and the radioactive material outside.” The site recommends staying inside for at least 24 hours, unless authorities recommend coming out sooner.

The sheltering directives go against the basic human instinct to flee and to reunite with family members as quickly as possible, emergency preparedness officials acknowledge. But parents are directed to leave their kids in school or day care, rather than risk driving to them in the radiation-laden atmosphere. “The response we got over and over again from people was ‘Thank God somebody is finally doing something about this.”

When the Los Angeles area conducted a nuclear-threat exercise in 2010 called Operation Golden Phoenix, Lawrence Livermore’s health physicist Buddemeier presented a model of a possible terrorist attack near Universal Studios Hollywood. His findings showed that 285,000 could die or get radiation sickness. But the vast majority of those, about 240,000, would be spared if they could find their way to basements or other more substantial shelters.

Those findings are common knowledge among public health officials and the subject of routine meetings like the one last month near Washington, D.C., of the National Council on Radiation Protection. Yet there is a “gap” between expert knowledge about these best practices and “getting it all the way into the public consciousness ... to keep them and their families safe,” Buddemeier said.

A man wearing protective clothing emerges from a fallout shelter in Medford, Massachusetts in 1961. AP

Deferring to the feds

The cities most often mentioned as possible targets of a nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) from North Korea are Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle. All three rely on the federal government to inform the public about how to prepare for a potential nuclear attack.

Barb Graff, director of Seattle’s Office of Emergency Management, said the city polled residents several years ago and found that they would hear and respond to messages about earthquakes and other threats but would “shut down,” and not take any preparatory action, when informed about nuclear threats.

RELATED: North Korea Detains Third American Citizen, Officials Say

advertisement

“It’s a hard discussion,” Graff said. “How do we pay attention to something we know is important but might cause people to shut down and not take any action if they are informed about it.”

Her department has received only a few calls in recent weeks, in response to the Korean nuclear provocations. Those residents were referred to Ready.gov. Los Angeles and San Francisco, similarly, refer inquiries to the federal government.

A proactive approach at the local level

Taking perhaps the most aggressive stance toward public notification anywhere in America is Ventura County in Southern California. The county's health department launched a campaign starting in 2013 to inform citizens about what to do in a nuclear attack. The county created an 18-page educational pamphlet, four videos and a curriculum for schools and a series of community meetings.

At the center of the campaign was the message "Get inside, stay inside, stay tuned." Dr. Robert Levin, the public health medical director for Ventura County, who led the effort, said concerns about terrifying the public didn't come to pass. "The response we got over and over again from people was ‘Thank God somebody is finally doing something about this,'" Levin said.

At the annual meeting last month of the National Council on Radiation Protection — a group of public health and emergency officials — the Ventura officials' efforts were welcomed with repeated applause.

by James Rainey

The threats seem to come almost daily now out of North Korea — ballistic missile firings, preparations to test a nuclear bomb and routine bravado. In April, state-owned media in the rogue nation vowed a “super mighty preemptive strike,” one that will reduce the U.S. to “ashes.”

On Saturday, residents in Hawaii were sent into a panic when they received alerts on their mobile phones and televisions warning that a ballistic missile was on its way. The warning, which claimed "this is not a drill," quickly prompted officials to say minutes later that it was sent in error.

Meanwhile, American weapons experts believe Pyongyang is likely a few years from having the capability of firing a nuclear–equipped missile that can reach the U.S. mainland.

Yet some leading emergency response planners view the persistent menace of North Korea as a new opportunity: reason to alert the American public that a limited nuclear attack can be survivable, with a few precautions.

North Korea Threat Growing or Just Saber-Rattling?

The simplest of the warnings is: "Don’t run. Get inside." Sheltering in place, beneath as many layers of protection as possible, is the best way to avoid the radiation that would follow a nuclear detonation.

That conclusion has been the consensus of the U.S. emergency and public health establishments for years, though national, state and local governments generally have been less than aggressive about putting the word out to the public. “The goal is to put as many walls and as much concrete, brick and soil between you and the radioactive material outside.”

Officials at the Federal Emergency Management Agency and Department of Homeland Security say the nuclear safety directives are available, including online at Ready.gov, but they have not broadcast them more widely. Asked about spreading the word beyond the website, a FEMA spokesperson emailed a terse response: "At this time time there are no specific plans to do any messaging on this topic."

School children and their teacher peer from beneath a table during a state-wide air raid test in Newark, New Jersey, in 1952. Bettmann / Getty Images

Part of the reticence has been out of a fear of alarming the public and part has been an attempt to balance education about “radiation safety” with other messages about threats like earthquakes, hurricanes and floods, say academics who advise the government.

“There is a lot of fatalism on this subject, the feeling that there will be untold death and destruction and there is nothing to be done,” said Irwin Redlener, director of Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness. “But the thing that is frustrating for me is that, with some very simple public messaging, we could save hundreds of thousands of lives in a nuclear detonation.”

Duck-and-cover drills a thing of the past

Brooke Buddemeier, a nationally-recognized expert on nuclear disaster preparedness from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, said that following the 9/11 attacks, Americans may have suffered a kind of “preparedness fatigue.”

“There was so much information that came out altogether,” Buddemeier said, “but then it’s kind of hard to fit information about nuclear terrorism in with warnings about earthquakes and hurricanes and wildfires and all other emergencies that happen on a regular basis.”

The last time that the threat of imminent nuclear attack gripped the American conscious, John F. Kennedy was in the White House. But duck-and-cover drills soon became a thing of the past and at-home fallout shelters are a rarity.

Local governments abandoned the mass public shelters they built during the Cold War. Parking garages beneath the Los Angeles Civic Center and a subterranean vault beneath a Seattle freeway overpass are no longer designated as safe zones for a retreating public.

While North Korean provocations have received the most attention in recent weeks, government officials remain at least as concerned about the possibility of an attack by terrorists or other “non-state” actors. In these scenarios, a nuclear device might be secreted into a ship, or some other delivery device, and exploded at ground level.

The largest nuclear blasts would create a fireball a mile in diameter and temperatures as hot as the surface of the sun, followed quickly by winds greater than the force of a hurricane, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. (North Korea’s past nuclear tests have been far smaller, with the largest an estimated 10 kilotons, less than either of the atomic bombs used on Japan in World War II). Radioactive fallout would be carried for miles by the jet stream and surface winds. While little might be done for immediate blast victims, researchers say that the public’s response will be crucial.

Trump to U.N. Security Council Diplomats: Remove 'Blindfolds' on North Korea

Resist the instinct to run for the hills

Years of novels, television and movie dramatizations have popularized visions of nuke victims flowing out of cities in unruly masses, seeking out radiation-free air. But experts say that finding a route to safety would range from difficult to impossible, given the droves who would be gridlocking freeways.

Survivors of an immediate blast would be much better served by finding cover. A car is better than the open air, while most houses are considerably safer than a car, particularly if there is room to hunker down in a basement.

“Go as far below ground as possible or in the center of a tall building,” says Ready.gov, the website created by FEMA and the Department of Homeland Security. “The goal is to put as many walls and as much concrete, brick and soil between you and the radioactive material outside.” The site recommends staying inside for at least 24 hours, unless authorities recommend coming out sooner.

The sheltering directives go against the basic human instinct to flee and to reunite with family members as quickly as possible, emergency preparedness officials acknowledge. But parents are directed to leave their kids in school or day care, rather than risk driving to them in the radiation-laden atmosphere. “The response we got over and over again from people was ‘Thank God somebody is finally doing something about this.”

When the Los Angeles area conducted a nuclear-threat exercise in 2010 called Operation Golden Phoenix, Lawrence Livermore’s health physicist Buddemeier presented a model of a possible terrorist attack near Universal Studios Hollywood. His findings showed that 285,000 could die or get radiation sickness. But the vast majority of those, about 240,000, would be spared if they could find their way to basements or other more substantial shelters.

Those findings are common knowledge among public health officials and the subject of routine meetings like the one last month near Washington, D.C., of the National Council on Radiation Protection. Yet there is a “gap” between expert knowledge about these best practices and “getting it all the way into the public consciousness ... to keep them and their families safe,” Buddemeier said.

A man wearing protective clothing emerges from a fallout shelter in Medford, Massachusetts in 1961. AP

Deferring to the feds

The cities most often mentioned as possible targets of a nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) from North Korea are Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle. All three rely on the federal government to inform the public about how to prepare for a potential nuclear attack.

Barb Graff, director of Seattle’s Office of Emergency Management, said the city polled residents several years ago and found that they would hear and respond to messages about earthquakes and other threats but would “shut down,” and not take any preparatory action, when informed about nuclear threats.

RELATED: North Korea Detains Third American Citizen, Officials Say

advertisement

“It’s a hard discussion,” Graff said. “How do we pay attention to something we know is important but might cause people to shut down and not take any action if they are informed about it.”

Her department has received only a few calls in recent weeks, in response to the Korean nuclear provocations. Those residents were referred to Ready.gov. Los Angeles and San Francisco, similarly, refer inquiries to the federal government.

A proactive approach at the local level

Taking perhaps the most aggressive stance toward public notification anywhere in America is Ventura County in Southern California. The county's health department launched a campaign starting in 2013 to inform citizens about what to do in a nuclear attack. The county created an 18-page educational pamphlet, four videos and a curriculum for schools and a series of community meetings.

At the center of the campaign was the message "Get inside, stay inside, stay tuned." Dr. Robert Levin, the public health medical director for Ventura County, who led the effort, said concerns about terrifying the public didn't come to pass. "The response we got over and over again from people was ‘Thank God somebody is finally doing something about this,'" Levin said.

At the annual meeting last month of the National Council on Radiation Protection — a group of public health and emergency officials — the Ventura officials' efforts were welcomed with repeated applause.

Rep. Kinzinger: U.S. Needs 'Credible Military Option' Against North Korea

North Korea and the need to know

The question of how government and individuals would respond if a nuclear strike hit the U.S. has become more pressing with the revelation, reported last week by NBC News, that experts believe America's missile shield system is far from foolproof. The anti-missile defense depends on the ability of America’s own rockets — based in Alaska and at Vandenberg Air Force Base on California’s Central Coast — to shoot incoming rockets out of the sky.

Tests of the “bullet-shooting-a-bullet” technology have not always succeeded, experts noted. And that's despite the fact that the tests have been conducted under optimum conditions, without the secret launch times and diversionary technology that enemy weapons would likely employ.

David Ropeik, a some-time instructor at the Harvard School of Public Health and an expert in risk assessment said that most public information campaigns about nuclear preparedness have been "too passive" and "not adequate." The ongoing threats from North Korea "create a huge opportunity to get this on our radar screen." Ropeik added: "The information is out there, most people just need to be alerted that it is there."

North Korea and the need to know

The question of how government and individuals would respond if a nuclear strike hit the U.S. has become more pressing with the revelation, reported last week by NBC News, that experts believe America's missile shield system is far from foolproof. The anti-missile defense depends on the ability of America’s own rockets — based in Alaska and at Vandenberg Air Force Base on California’s Central Coast — to shoot incoming rockets out of the sky.

Tests of the “bullet-shooting-a-bullet” technology have not always succeeded, experts noted. And that's despite the fact that the tests have been conducted under optimum conditions, without the secret launch times and diversionary technology that enemy weapons would likely employ.

David Ropeik, a some-time instructor at the Harvard School of Public Health and an expert in risk assessment said that most public information campaigns about nuclear preparedness have been "too passive" and "not adequate." The ongoing threats from North Korea "create a huge opportunity to get this on our radar screen." Ropeik added: "The information is out there, most people just need to be alerted that it is there."

Redlener, of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness, said informing the public has been slowed by concerns about creating undue alarm. But a worse failing would be to leave people in the dark about simple precautions that could save lives, he said.

“The public should be treated as adults,” Redlener said. “We live in a complicated world and we want people to be prepared.”

No comments:

Post a Comment