GLOBAL

A letter calling for his resignation shows how serious his crisis of credibility has become.

REUTERS

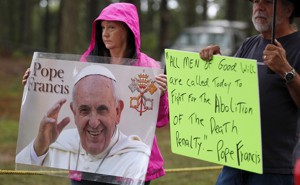

Pope Francis’s credibility has taken a major hit as the crisis over clergy sex abuse continues to roil the Catholic Church. Following weeks of horrifying revelations about the Church’s long-standing mismanagement of allegations against priests, the pope visited Ireland this weekend, asking forgiveness for a long list of “abuses” and “exploitation.” Reporters observed that crowds were nowhere near as large for Francis as they were for John Paul II, the last pope to visit Ireland. Protesters also called for more extensive apologies.

Then, toward the end of Francis’s trip, a prominent archbishop published a letter claiming the pope knew about—and covered up—the wrongdoings of Theodore McCarrick, the former cardinal of Washington who has been accused of sexually harassing adult seminarians and abusing a child over a period of years. Carlo Maria Viganò, the former representative of the Vatican in the United States, called on Francis to resign, along with other “cardinals and bishops who covered up McCarrick’s abuses.”

The pope refused to address these allegations on Sunday, telling reporters, “I will not say a word about this.” One of his prominent allies in the United States, Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, questioned the veracity of several of Viganò’s claims in a statement. And the pope’s defenders have characterized the letter as a smear against Francis, in part because of Viganò’s past clashes with the pope. The letter reflects the simmering discontent of conservative clergy in Rome, who dislike Francis’s inclination towards reform.

Even if critics are correct that this letter was colored by vicious hierarchy infighting, it has exposed the extent of the vitriol surrounding the pope’s handling of sexual abuse. It’s not just the pope’s political enemies who have questioned his credibility. Francis is also facing a lack of trust among the faithful in the Church.

Pope Francis’s credibility has taken a major hit as the crisis over clergy sex abuse continues to roil the Catholic Church. Following weeks of horrifying revelations about the Church’s long-standing mismanagement of allegations against priests, the pope visited Ireland this weekend, asking forgiveness for a long list of “abuses” and “exploitation.” Reporters observed that crowds were nowhere near as large for Francis as they were for John Paul II, the last pope to visit Ireland. Protesters also called for more extensive apologies.

Then, toward the end of Francis’s trip, a prominent archbishop published a letter claiming the pope knew about—and covered up—the wrongdoings of Theodore McCarrick, the former cardinal of Washington who has been accused of sexually harassing adult seminarians and abusing a child over a period of years. Carlo Maria Viganò, the former representative of the Vatican in the United States, called on Francis to resign, along with other “cardinals and bishops who covered up McCarrick’s abuses.”

The pope refused to address these allegations on Sunday, telling reporters, “I will not say a word about this.” One of his prominent allies in the United States, Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, questioned the veracity of several of Viganò’s claims in a statement. And the pope’s defenders have characterized the letter as a smear against Francis, in part because of Viganò’s past clashes with the pope. The letter reflects the simmering discontent of conservative clergy in Rome, who dislike Francis’s inclination towards reform.

Even if critics are correct that this letter was colored by vicious hierarchy infighting, it has exposed the extent of the vitriol surrounding the pope’s handling of sexual abuse. It’s not just the pope’s political enemies who have questioned his credibility. Francis is also facing a lack of trust among the faithful in the Church.

KORI SCHAKE

[Catholics are desperate for tangible reforms on clergy sex Abuse]

In recent years, few countries have been hit harder by scandals in the Catholic Church than Ireland. Clergy failed to report allegations of child sexual abuse against dozens of priests over decades, according to an independent audit. Historians and investigators have slowly uncovered years of abuses at so-called mother and baby homes, where unwed pregnant women were often sent against their will. The facts were particularly gruesome in the town of Tuam, where the remains of dead infants and fetuses were found in the sewer system next to a home run by nuns.

So perhaps it was inevitable that Francis’s trip to Ireland, which marked a triennial global gathering of families in Dublin, was filled with grave reminders of Ireland’s troubled past. Protesters held vigils throughout the country for victims of clergy sex abuse. The pope met with a number of victims. And in his closing remarks, Francis apologized for “abuses of power, conscience, and sexual abuse,” and begged forgiveness for leaders in the Church who failed to report abuse or show compassion to victims. Significantly, he asked forgiveness from the single mothers who had been sent away to homes, and who were later condemned for wanting to be with their children.

But the pope’s conciliatory tone was also mixed with defensiveness, and moments of what might be described as naiveté. According to The New York Times, he told reporters that he had never heard of Ireland’s mother and baby homes before this visit. He also rejected the notion that the Church needs a standing court to handle allegations against priests, and he blamed journalists for promoting an “atmosphere of guilt” towards clergy accused of abuse. He was most defensive about Viganò’s letter, telling reporters to “make your own judgment. … I believe the document speaks for itself.”

The 11-page letter, which was published by the conservative outlet National Catholic Register, contains a number shocking allegations.*Viganò claims that a series of Vatican representatives in the U.S. knew about the allegations against McCarrick as early as two decades ago and reported them to the Holy See. He alleges that Pope Benedict XVI sanctioned McCarrick—although no sanctions were ever made public—and that Francis then disregarded those sanctions by making McCarrick his “trusted counselor.”

After a series of unsubstantiated allegations against a number of prominent American clerics—some of which are openly speculative and contain conspiratorial language about bishops “[promoting] the LGBT agenda” and supporting pro-abortion politicians—Viganò calls on Francis to resign.

The letter is significant because of the seriousness of its charges and the prominence of its author. But this particular archbishop also has a long, tense history with Francis. In 2016, Viganò was pushed out of his post as the apostolic nuncio, a high-ranking diplomatic representative, to the United States. The ouster came several months after Pope Francis’s trip to the U.S., during which Viganò was involved in a minor scandal: He coordinated a visit between the pope and Kim Davis, the Kentucky clerk who famously refused to perform gay marriages. The Vatican later distanced itself from this visit, which had seemed to suggest that Francis was giving his support to conservative culture wars in America.

[The Vatican’s internal fight over Kim Davis and the pope]

Notably, Francis has caught significant criticism not only from conservative clergy like Viganò, but also from progressives in the Church, who say that he has not taken steps to address the lingering wounds of sex abuse. Some of his loudest critics have been sex-abuse victims, who have been hurt by the pope’s past dismissals of clergy abuse. Although steps have been taken in some countries over the last two decades to educate clergy and put safety procedures in place, those have been implemented unevenly, and the past several weeks have made it evident that the legacy of abuse remains raw.

Ultimately, then, this is what matters: The latest sexual-abuse revelations threaten to undermine the pope’s credibility among everyday believers who feel betrayed by their Church. The sexual-abuse crisis is now center stage in Francis’s papacy. What he chooses to do—and not do—about the crisis next may have long-term repercussions for his reputation.

* This article originally stated that Archbishop Viganò’s allegations were published in theNational Catholic Reporter, rather than theNational Catholic Register. We regret the error.

[Catholics are desperate for tangible reforms on clergy sex Abuse]

In recent years, few countries have been hit harder by scandals in the Catholic Church than Ireland. Clergy failed to report allegations of child sexual abuse against dozens of priests over decades, according to an independent audit. Historians and investigators have slowly uncovered years of abuses at so-called mother and baby homes, where unwed pregnant women were often sent against their will. The facts were particularly gruesome in the town of Tuam, where the remains of dead infants and fetuses were found in the sewer system next to a home run by nuns.

So perhaps it was inevitable that Francis’s trip to Ireland, which marked a triennial global gathering of families in Dublin, was filled with grave reminders of Ireland’s troubled past. Protesters held vigils throughout the country for victims of clergy sex abuse. The pope met with a number of victims. And in his closing remarks, Francis apologized for “abuses of power, conscience, and sexual abuse,” and begged forgiveness for leaders in the Church who failed to report abuse or show compassion to victims. Significantly, he asked forgiveness from the single mothers who had been sent away to homes, and who were later condemned for wanting to be with their children.

But the pope’s conciliatory tone was also mixed with defensiveness, and moments of what might be described as naiveté. According to The New York Times, he told reporters that he had never heard of Ireland’s mother and baby homes before this visit. He also rejected the notion that the Church needs a standing court to handle allegations against priests, and he blamed journalists for promoting an “atmosphere of guilt” towards clergy accused of abuse. He was most defensive about Viganò’s letter, telling reporters to “make your own judgment. … I believe the document speaks for itself.”

The 11-page letter, which was published by the conservative outlet National Catholic Register, contains a number shocking allegations.*Viganò claims that a series of Vatican representatives in the U.S. knew about the allegations against McCarrick as early as two decades ago and reported them to the Holy See. He alleges that Pope Benedict XVI sanctioned McCarrick—although no sanctions were ever made public—and that Francis then disregarded those sanctions by making McCarrick his “trusted counselor.”

After a series of unsubstantiated allegations against a number of prominent American clerics—some of which are openly speculative and contain conspiratorial language about bishops “[promoting] the LGBT agenda” and supporting pro-abortion politicians—Viganò calls on Francis to resign.

The letter is significant because of the seriousness of its charges and the prominence of its author. But this particular archbishop also has a long, tense history with Francis. In 2016, Viganò was pushed out of his post as the apostolic nuncio, a high-ranking diplomatic representative, to the United States. The ouster came several months after Pope Francis’s trip to the U.S., during which Viganò was involved in a minor scandal: He coordinated a visit between the pope and Kim Davis, the Kentucky clerk who famously refused to perform gay marriages. The Vatican later distanced itself from this visit, which had seemed to suggest that Francis was giving his support to conservative culture wars in America.

[The Vatican’s internal fight over Kim Davis and the pope]

Notably, Francis has caught significant criticism not only from conservative clergy like Viganò, but also from progressives in the Church, who say that he has not taken steps to address the lingering wounds of sex abuse. Some of his loudest critics have been sex-abuse victims, who have been hurt by the pope’s past dismissals of clergy abuse. Although steps have been taken in some countries over the last two decades to educate clergy and put safety procedures in place, those have been implemented unevenly, and the past several weeks have made it evident that the legacy of abuse remains raw.

Ultimately, then, this is what matters: The latest sexual-abuse revelations threaten to undermine the pope’s credibility among everyday believers who feel betrayed by their Church. The sexual-abuse crisis is now center stage in Francis’s papacy. What he chooses to do—and not do—about the crisis next may have long-term repercussions for his reputation.

* This article originally stated that Archbishop Viganò’s allegations were published in theNational Catholic Reporter, rather than theNational Catholic Register. We regret the error.

EMMA GREEN is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers politics, policy, and religion.

No comments:

Post a Comment