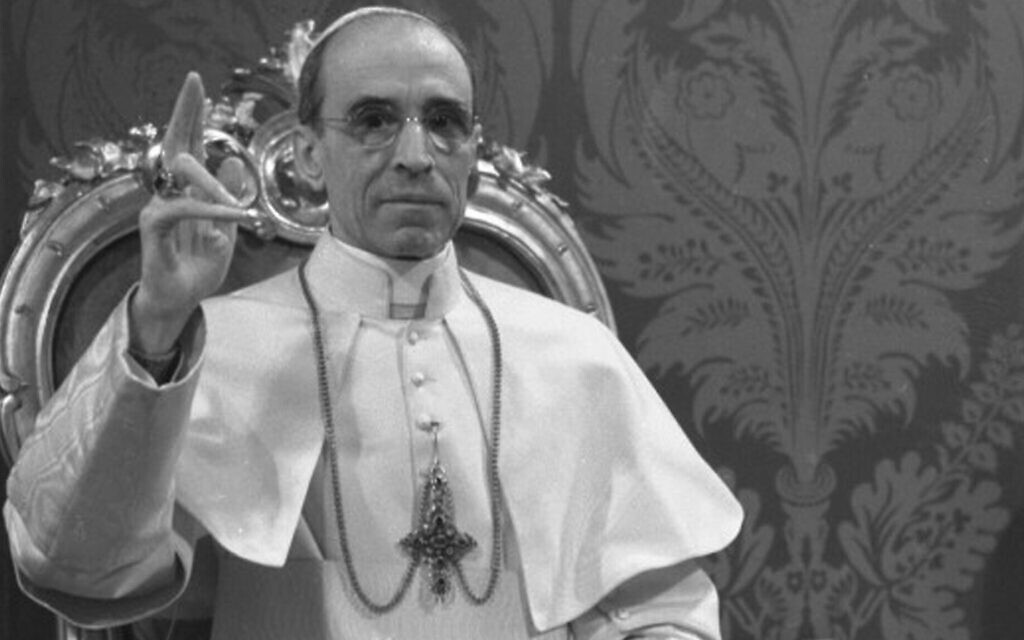

Pope Pius XII (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

ABIDING CATHOLIC CONTROVERSY MAY SOON GET CONCRETE ANSWERS

Documentary confronts cost of Pope Pius XII’s ‘Holy Silence’ during Holocaust

Premiering January 21 ahead of the imminent opening of the Secret Vatican Archives for 1939-1958, film provides historical context for 17 million pages of documents to be released

By RENEE GHERT-ZAND 21 Jan 2020, 1:56 am17

Last year, Pope Francis announced that on March 2, 2020, he would open the Vatican Archives for the pontificate of Pius XII. It is a long awaited move, as controversy has swirled for decades over Pius XII’s lack of action to save Jewish lives during the Holocaust. Indeed, the canonization of Pius XII has been delayed – if not totally derailed — due to questions about his reluctance to use the Church’s moral influence during this dark period.

“The Church is not afraid of history,” proclaimed Pope Francis in his official announcement of the archives’ scheduled opening.

Vatican archivists, led by Bishop Sergio Pagano, prefect of the Vatican Secret Archives, have prepared for years for this ahead-of-schedule opening (archives are usually opened 70 years after the end of a pontificate). In addition to the Vatican Secret Archives (recently renamed the Vatican Apostolic Archives), a number of other archives from the pontificate of Pius XII from 1939 to 1958 will be opened. It will take years for scholars to comb through the approximately 17 million pages of documents expected to be released.

Steven Pressman (Courtesy of USHMM)

“I was determined not to make a film that came across solely as an attack on the Catholic Church, though it is critical of Pius XII,” Pressman said.

In “Holy Silence,” Dr. Suzanne Brown-Fleming, director of international academic programs at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and author of “The Holocaust and Catholic Conscience” states that Nazi leaders would not have cared what the Pope said. However, Pius XII could have done more to raise the moral consciousness of Reich citizens.

“I’m thinking here about those 21 million German Catholics who had to cooperate and support the Nazi regime for it to function on a day to day level. Maybe they would have behaved differently. Maybe they would have sheltered a Jewish family. Maybe they would have responded differently to an order on the battlefield, or responded to the Nazi thug in their neighborhood, or when their own church was being attacked,” Brown-Fleming says in the film.

A pragmatic decision?

The pope believed that the Nazis would win the war and control most of Europe as a result. Therefore, American requests that he support the Allies fell on deaf ears. In his public statements and radio addresses, the pontiff decried violence and expressed sorrow for its victims, but he did not explicitly mention the Jews. In one speech, he entreated the combatants not to bomb the art and architectural treasures of Rome and Vatican City, but didn’t express much concern about protecting people.

The film indicates that there is currently no clearcut evidence that the Vatican warned Jews of impending deportation when Germany occupied Italy in 1943, or that the Pope issued a directive to Catholic institutions to shelter Jews. In one instance, on October 16, 1943, 1,259 Jews were arrested within meters of Vatican City.

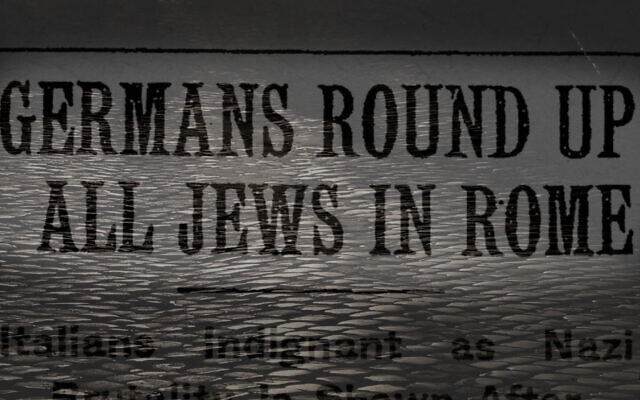

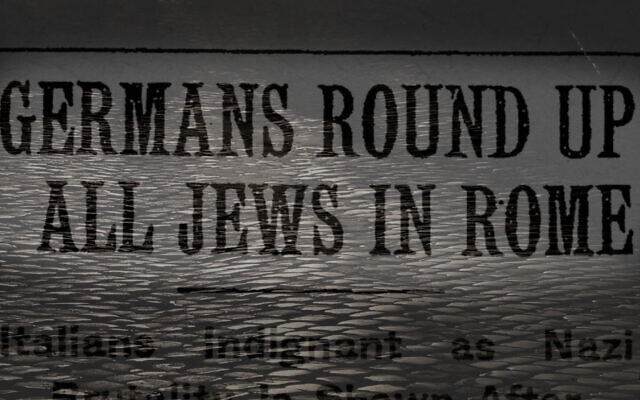

Newspaper headline from October 1943 (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Pius XII viewed his role as that of peacemaker. In a missive to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt he wrote, “As vicar on earth of the Prince of Peace, we have dedicated our efforts and our solicitude to the purpose of maintaining peace, and afterwards reestablishing it. Heedless of momentary lack of success and the difficulties involved, we are continuing to follow along the path marked out to us by our apostolic mission.”

However, there is a second equally important question posed, which is whether history would have been different had Pius XII’s predecessor, Pius XI, not died in February 1939 while on the verge of presenting a draft encyclical denouncing racism and anti-Semitism to an assembly of bishops.

Pople Pius XI (in hat) (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Pius XI, who had a late in life change of heart about confronting anti-Semitism and fascism, had throughout the 1920s and 1930s relied on the advice of his secretary of state Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli — who later became Pope Pius XII. Pacelli had lived and represented the Vatican in Germany for many years, and therefore had an affinity for the country.

“There was no evidence that Pius XII was anti-Semitic, but he was clearly pro-German,” said Peter Eisner, journalist and author of “The Pope’s Last Crusade: How an American Jesuit Helped Pope Pius XI’s Campaign to Stop Hitler.”

John LaFarge, SJ (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

In the first half of “Holy Silence,” Pressman tells how Pius XI secretly summoned in 1938 an American Jesuit priest named John LaFarge known for his activism against racism and anti-Semitism. The pope asked LaFarge to draft an encyclical that would effectively counter everything Hitler and Nazi Germany stood for. LaFarge did so, and gave it to a Jesuit superior to deliver to Pius XI. Then things went silent; months passed and LaFarge heard nothing back from the pope.

“Half the Vatican was against the encyclical,” Eisner said, in explaining why it took so long to reach the desk of Pius XI.

Pius XI died on February 10, 1939, immediately before he was to unveil his encyclical to the bishops and lobby for its adoption. Pius XII was inaugurated, and according to “Holy Silence,” the draft encyclical was destroyed.

A tale worthy of Sherlock Holmes

But this is not exactly what happened. Eisner told The Times of Israel that in the early 1970s, a Jesuit priest working on files at Georgetown University left by LaFarge after his death in 1963 discovered a draft copy of the encyclical. Then in 1995, a book was published in France based on the discovered document.

Peter Eisner (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

However, when Eisner went looking for the encyclical at Georgetown, it wasn’t there. He discovered it at Boston College. A priest named Edward Stanton had borrowed the LaFarge files from Georgetown in the 1980s and had suffered a fatal heart attack before returning them.

“I found the original English draft and a letter from LaFarge to Pope Pius XI asking what was happening with it,” Eisner said.

Following the inauguration of Pius XII, LaFarge had been ordered to destroy the draft encyclical and tell no one about it. He kept quiet for many years, but in the months before his death, he told his Jesuit colleagues the whole story.

According to Eisner, German and French versions of the draft encyclical also survived in the Vatican archives, but all documentation surrounding the writing of and plans for the document were destroyed.

Encyclical may have saved ‘perhaps millions of lives’

Eisner is not the only one who believes that Pius XI would have issued the encyclical, and that it could have made a major difference for at least some of European Jewry.

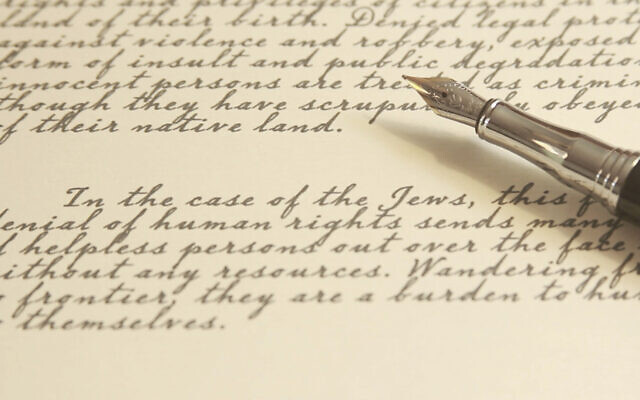

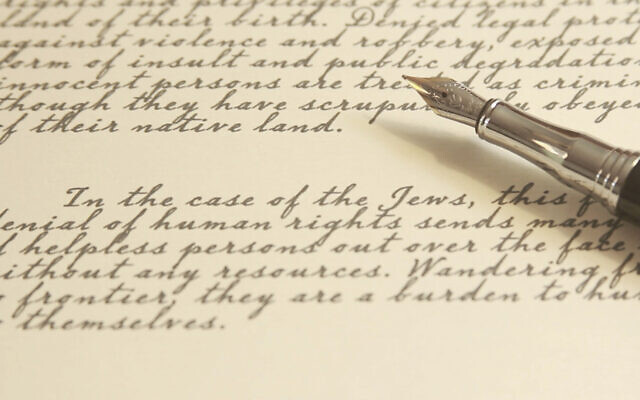

Reproduction of papal encyclical drafted for Pope Pius XI by John LaFarge, SJ (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

After reviewing what became known as “The Hidden Encyclical,” The National Catholic Reporter published an editorial on December 15, 1972 stating: “Considering that Hitler had only begun to move into full-scale persecution of the Jews, and had not yet begun planned extermination; considering that Italy had only begun to copy Germany’s racial laws; considering the persecution of Jews throughout history; considering the difficulty, especially in Europe, of launching a similar wide-scale attack on Catholics; and considering the moral weight of the papacy, especially at that point in history — considering all this, we must conclude that the publication of the encyclical draft at the time it was written may have saved hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of lives.”

Of course, we will never know for sure what would have happened. But the opening of the Vatican Secret Archive for the pontificate of Pius XII will hopefully provide answers to questions scholars have been unable to answer thus far.

Dr. Suzanne Brown-Fleming (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Brown-Fleming is one of a team of five from the USHMM that will be heading to Rome beginning March 2. She has many questions, but they mostly boil down to what did Pope Pius XII and the Holy See know, when did they know it, and what did they do about it?

The pope’s lack of action already speaks louder than the words in the 17 million documents that will be soon be released, but there will certainly be nuanced information to broaden and deepen our understanding of what really happened.

Perhaps historians will uncover the truth: Was Pius XII only protecting the Church, or was he motivated by anti-Semitic animus? It’s a question audiences of all faiths can ponder as they watch Pressman’s film and reflect on the cost of remaining silent.

ABIDING CATHOLIC CONTROVERSY MAY SOON GET CONCRETE ANSWERS

Documentary confronts cost of Pope Pius XII’s ‘Holy Silence’ during Holocaust

Premiering January 21 ahead of the imminent opening of the Secret Vatican Archives for 1939-1958, film provides historical context for 17 million pages of documents to be released

By RENEE GHERT-ZAND 21 Jan 2020, 1:56 am17

Last year, Pope Francis announced that on March 2, 2020, he would open the Vatican Archives for the pontificate of Pius XII. It is a long awaited move, as controversy has swirled for decades over Pius XII’s lack of action to save Jewish lives during the Holocaust. Indeed, the canonization of Pius XII has been delayed – if not totally derailed — due to questions about his reluctance to use the Church’s moral influence during this dark period.

“The Church is not afraid of history,” proclaimed Pope Francis in his official announcement of the archives’ scheduled opening.

Vatican archivists, led by Bishop Sergio Pagano, prefect of the Vatican Secret Archives, have prepared for years for this ahead-of-schedule opening (archives are usually opened 70 years after the end of a pontificate). In addition to the Vatican Secret Archives (recently renamed the Vatican Apostolic Archives), a number of other archives from the pontificate of Pius XII from 1939 to 1958 will be opened. It will take years for scholars to comb through the approximately 17 million pages of documents expected to be released.

Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

In the meantime, the public can learn more about the historical background to the events reflected in these documents from a new film, “Holy Silence,” which will have its world premiere on January 21 at the Miami Jewish Film Festival.

Filmmaker Steven Pressman began work on “Holy Silence” in 2017 without regard to any possible opening of the Vatican Secret Archives. Nonetheless he is obviously pleased about the favorable timing of the film’s completion and release.

“To be honest, I woke up that morning [March 2, 2019] to the news about the opening of the archives [in a year] and felt total panic… But then I realized that the timing is actually good and that I am very lucky,” Pressman told The Times of Israel.

The San Francisco-based Pressman enjoyed success with his first Nazi Germany-era documentary, “50 Children,” but had for the most part been unaware of the Vatican’s position during World War II. He discovered that the subject of Pius XII and the Holocaust had been thoroughly covered in books, but not in film.

Pressman, 64, reached out to many of the various authors as part of his research. Commentary by at least a dozen of these scholars, journalists and clergy members is interspersed throughout the film with clips of archival film footage and several dramatic reenactments.

To provide a unique framing device for “Holy Silence,” Pressman honed the American angle of the story. He focuses on American figures — clerical, official and political — who tried to influence the Vatican during the 1930s and during the war. Pressman also examines the influence of homegrown anti-Semitism, like that of Fr. Charles Coughlin on American Catholics and on American-European relations.

The major question posed by “Holy Silence” is whether Pius XII did all he could to counter Nazi Germany and save Jews. The answer is clearly no based on the majority of viewpoints expressed by the experts interviewed.

In the meantime, the public can learn more about the historical background to the events reflected in these documents from a new film, “Holy Silence,” which will have its world premiere on January 21 at the Miami Jewish Film Festival.

Filmmaker Steven Pressman began work on “Holy Silence” in 2017 without regard to any possible opening of the Vatican Secret Archives. Nonetheless he is obviously pleased about the favorable timing of the film’s completion and release.

“To be honest, I woke up that morning [March 2, 2019] to the news about the opening of the archives [in a year] and felt total panic… But then I realized that the timing is actually good and that I am very lucky,” Pressman told The Times of Israel.

The San Francisco-based Pressman enjoyed success with his first Nazi Germany-era documentary, “50 Children,” but had for the most part been unaware of the Vatican’s position during World War II. He discovered that the subject of Pius XII and the Holocaust had been thoroughly covered in books, but not in film.

Pressman, 64, reached out to many of the various authors as part of his research. Commentary by at least a dozen of these scholars, journalists and clergy members is interspersed throughout the film with clips of archival film footage and several dramatic reenactments.

To provide a unique framing device for “Holy Silence,” Pressman honed the American angle of the story. He focuses on American figures — clerical, official and political — who tried to influence the Vatican during the 1930s and during the war. Pressman also examines the influence of homegrown anti-Semitism, like that of Fr. Charles Coughlin on American Catholics and on American-European relations.

The major question posed by “Holy Silence” is whether Pius XII did all he could to counter Nazi Germany and save Jews. The answer is clearly no based on the majority of viewpoints expressed by the experts interviewed.

Steven Pressman (Courtesy of USHMM)

“I was determined not to make a film that came across solely as an attack on the Catholic Church, though it is critical of Pius XII,” Pressman said.

In “Holy Silence,” Dr. Suzanne Brown-Fleming, director of international academic programs at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and author of “The Holocaust and Catholic Conscience” states that Nazi leaders would not have cared what the Pope said. However, Pius XII could have done more to raise the moral consciousness of Reich citizens.

“I’m thinking here about those 21 million German Catholics who had to cooperate and support the Nazi regime for it to function on a day to day level. Maybe they would have behaved differently. Maybe they would have sheltered a Jewish family. Maybe they would have responded differently to an order on the battlefield, or responded to the Nazi thug in their neighborhood, or when their own church was being attacked,” Brown-Fleming says in the film.

A pragmatic decision?

The pope believed that the Nazis would win the war and control most of Europe as a result. Therefore, American requests that he support the Allies fell on deaf ears. In his public statements and radio addresses, the pontiff decried violence and expressed sorrow for its victims, but he did not explicitly mention the Jews. In one speech, he entreated the combatants not to bomb the art and architectural treasures of Rome and Vatican City, but didn’t express much concern about protecting people.

The film indicates that there is currently no clearcut evidence that the Vatican warned Jews of impending deportation when Germany occupied Italy in 1943, or that the Pope issued a directive to Catholic institutions to shelter Jews. In one instance, on October 16, 1943, 1,259 Jews were arrested within meters of Vatican City.

Newspaper headline from October 1943 (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Pius XII viewed his role as that of peacemaker. In a missive to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt he wrote, “As vicar on earth of the Prince of Peace, we have dedicated our efforts and our solicitude to the purpose of maintaining peace, and afterwards reestablishing it. Heedless of momentary lack of success and the difficulties involved, we are continuing to follow along the path marked out to us by our apostolic mission.”

However, there is a second equally important question posed, which is whether history would have been different had Pius XII’s predecessor, Pius XI, not died in February 1939 while on the verge of presenting a draft encyclical denouncing racism and anti-Semitism to an assembly of bishops.

Pople Pius XI (in hat) (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Pius XI, who had a late in life change of heart about confronting anti-Semitism and fascism, had throughout the 1920s and 1930s relied on the advice of his secretary of state Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli — who later became Pope Pius XII. Pacelli had lived and represented the Vatican in Germany for many years, and therefore had an affinity for the country.

“There was no evidence that Pius XII was anti-Semitic, but he was clearly pro-German,” said Peter Eisner, journalist and author of “The Pope’s Last Crusade: How an American Jesuit Helped Pope Pius XI’s Campaign to Stop Hitler.”

John LaFarge, SJ (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

In the first half of “Holy Silence,” Pressman tells how Pius XI secretly summoned in 1938 an American Jesuit priest named John LaFarge known for his activism against racism and anti-Semitism. The pope asked LaFarge to draft an encyclical that would effectively counter everything Hitler and Nazi Germany stood for. LaFarge did so, and gave it to a Jesuit superior to deliver to Pius XI. Then things went silent; months passed and LaFarge heard nothing back from the pope.

“Half the Vatican was against the encyclical,” Eisner said, in explaining why it took so long to reach the desk of Pius XI.

Pius XI died on February 10, 1939, immediately before he was to unveil his encyclical to the bishops and lobby for its adoption. Pius XII was inaugurated, and according to “Holy Silence,” the draft encyclical was destroyed.

A tale worthy of Sherlock Holmes

But this is not exactly what happened. Eisner told The Times of Israel that in the early 1970s, a Jesuit priest working on files at Georgetown University left by LaFarge after his death in 1963 discovered a draft copy of the encyclical. Then in 1995, a book was published in France based on the discovered document.

Peter Eisner (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

However, when Eisner went looking for the encyclical at Georgetown, it wasn’t there. He discovered it at Boston College. A priest named Edward Stanton had borrowed the LaFarge files from Georgetown in the 1980s and had suffered a fatal heart attack before returning them.

“I found the original English draft and a letter from LaFarge to Pope Pius XI asking what was happening with it,” Eisner said.

Following the inauguration of Pius XII, LaFarge had been ordered to destroy the draft encyclical and tell no one about it. He kept quiet for many years, but in the months before his death, he told his Jesuit colleagues the whole story.

According to Eisner, German and French versions of the draft encyclical also survived in the Vatican archives, but all documentation surrounding the writing of and plans for the document were destroyed.

Encyclical may have saved ‘perhaps millions of lives’

Eisner is not the only one who believes that Pius XI would have issued the encyclical, and that it could have made a major difference for at least some of European Jewry.

Reproduction of papal encyclical drafted for Pope Pius XI by John LaFarge, SJ (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

After reviewing what became known as “The Hidden Encyclical,” The National Catholic Reporter published an editorial on December 15, 1972 stating: “Considering that Hitler had only begun to move into full-scale persecution of the Jews, and had not yet begun planned extermination; considering that Italy had only begun to copy Germany’s racial laws; considering the persecution of Jews throughout history; considering the difficulty, especially in Europe, of launching a similar wide-scale attack on Catholics; and considering the moral weight of the papacy, especially at that point in history — considering all this, we must conclude that the publication of the encyclical draft at the time it was written may have saved hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of lives.”

Of course, we will never know for sure what would have happened. But the opening of the Vatican Secret Archive for the pontificate of Pius XII will hopefully provide answers to questions scholars have been unable to answer thus far.

Dr. Suzanne Brown-Fleming (Courtesy of PerlePress Productions)

Brown-Fleming is one of a team of five from the USHMM that will be heading to Rome beginning March 2. She has many questions, but they mostly boil down to what did Pope Pius XII and the Holy See know, when did they know it, and what did they do about it?

The pope’s lack of action already speaks louder than the words in the 17 million documents that will be soon be released, but there will certainly be nuanced information to broaden and deepen our understanding of what really happened.

Perhaps historians will uncover the truth: Was Pius XII only protecting the Church, or was he motivated by anti-Semitic animus? It’s a question audiences of all faiths can ponder as they watch Pressman’s film and reflect on the cost of remaining silent.

No comments:

Post a Comment