The coronavirus crisis "will be even worse than the Great Recession by a factor of at least two," one mayor said.

Small businesses in Brooklyn, N.Y., and across the country have been closed for weeks during the coronavirus epidemic.Mark Lennihan / AP file

April 22, 2020, 7:11 AM EDT / Updated April 22, 2020, 3:34 PM EDT

By Allan Smith

Across the country, state and local governments are clamoring for the federal government to rescue them from what could quickly become a fiscal catastrophe, saying that they may need as much as three-quarters of a trillion dollars as the coronavirus pandemic dries up many of their revenue sources.

Though Democrats sought to include roughly $150 billion in funding to state and local governments in the latest coronavirus aid package, set to pass this week, it did not make it into the final bill. Already, Congress approved $150 billion in funding for state and local governments as part of earlier coronavirus legislative aid — assistance governors and local leaders said would ultimately not be enough.

A Congressional Research Service report last week on initial coronavirus aid said that "early evidence suggests that the COVID-19 economic shock will have a notable impact on state and local budgets," pointing to the "sizable share of economic output" that derives from state and local governments.

April 22, 2020, 7:11 AM EDT / Updated April 22, 2020, 3:34 PM EDT

By Allan Smith

Across the country, state and local governments are clamoring for the federal government to rescue them from what could quickly become a fiscal catastrophe, saying that they may need as much as three-quarters of a trillion dollars as the coronavirus pandemic dries up many of their revenue sources.

Though Democrats sought to include roughly $150 billion in funding to state and local governments in the latest coronavirus aid package, set to pass this week, it did not make it into the final bill. Already, Congress approved $150 billion in funding for state and local governments as part of earlier coronavirus legislative aid — assistance governors and local leaders said would ultimately not be enough.

A Congressional Research Service report last week on initial coronavirus aid said that "early evidence suggests that the COVID-19 economic shock will have a notable impact on state and local budgets," pointing to the "sizable share of economic output" that derives from state and local governments.

April 21, 202001:50

Linda Bilmes, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and a leading expert on public budgetary and financing issues, told NBC News that the nature of the crisis prevents states from raising new revenue in traditional ways.

"Can you increase property taxes, retail taxes, income taxes, special investments? Can you increase service fees? Well, no," she added. "Nobody's using services, toll roads. Can you expand the number of fees? Can you increase traffic violations? Well, nobody's driving."

These governments will need to instead lay off or furlough workers, reduce benefits, cancel projects, defer construction and maintenance, and more.

"But the problem is that by doing all of those kind of things and canceling a lot of those kind of capital projects, those are the things that create employment and activity in the community and in the economy," Bilmes said, adding, "It's certainly capable of derailing a recovery or creating a second wave of recession."

Already, governors, mayors and county executives are planning for substantial budget cuts. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat, slashed roughly $235 million in planned spending. In Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, estimates suggest that billions in projected revenue over the next year will vanish. At the county-level, the National Association of Counties estimates close to $150 billion in lost revenue.

Matthew Chase, executive director of the National Association of Counties, said counties are watching as revenue from sales and gas taxes, court filing fees and mortgage transactions evaporate. The losses mean "you're going to see a cut in the staff at the exact wrong time, when their residents actually are going to need more services."

State and local governments employ more than 10 percent of the overall U.S. workforce, including police officers, firefighters and public-school teachers. State governments heavily subsidize public universities and finance significant construction projects, while local governments handle everything from trash collection to filling potholes.

Nan Whaley, the mayor of Dayton, Ohio, said her administration felt the impact of the outbreak on its budget "right away," and quickly furloughed nearly a quarter of the city's employees and have since instituted a hiring freeze. She's asked her departments to provide guidance on what an 18 percent spending cut would look like, which she said would affect police, fire and trash pickup, among other services.

"In 2009, in the Great Recession, most midsized cities in the middle of the country were decimated. We cut like 40 percent of our employees then," said Whaley, a Democrat. "So we are on bare bones as it is."

This crisis, Whaley believes, "will be even worse than the Great Recession — by a factor of at least two."

In Oklahoma City, Mayor David Holt, a Republican, said his city faces budget cuts of 3.3 percent for police and firefighters and 11.25 percent for all other departments for the upcoming fiscal year. But Holt says his city is buoyed by a more than $100 million reserve fund.

"We're always prepared for bad stuff to happen," he said. "Nevertheless ... these are probably some of the biggest cuts here in Oklahoma City that we've taken in the last two decades."

Federal intervention will be needed within a couple of months, Holt said.

The National Governors Association has called for $500 billion in funding to state governments to account for budget shortfalls, while counties and mayors have called for an additional $250 billion in emergency relief. On Monday, Sens. Bill Cassidy, R-La., and Bob Menendez, D-N.J., unveiled a legislative proposal for $500 billion in state and local funding.

"In this crazy and political environment where you can't get Democrats and Republicans to agree on anything," New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, said, "all the governors agree and have said to Washington, 'Make sure you fund the states in any next bill you pass.'"

In three Rust Belt states, Govs. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania and Tony Evers of Wisconsin, all Democrats, wrote to President Donald Trump last week asking him to work with Congress to get states and localities more funding.

"Without this leadership, the damage to our state economies will be exacerbated by the cuts we know we will be forced to make," they said.

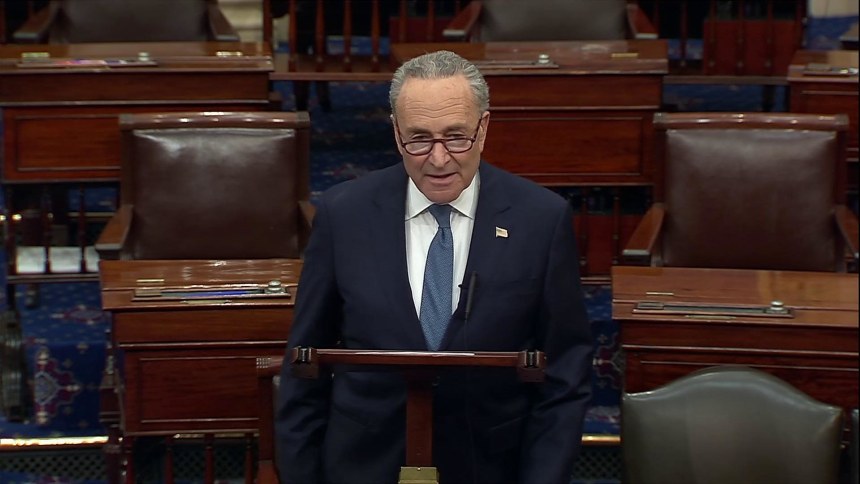

The boost won't be coming in this current round of coronavirus aid, though Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., sounded optimistic it would be included in a future aid package.

In a letter to senators, Schumer said he was "disappointed" the funding was not part of the upcoming bill but added that "as a part of this agreement, we were able to secure a commitment from (Treasury) Secretary Mnuchin that he will support additional state and local relief in the next COVID-19 legislation, as well as a provision providing the flexibility to use all past and future relief dollars to offset lost revenues."

However, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., seemed to throw cold water on the possibility of additional massive relief bills, telling reporters Tuesday he thinks "it's also time to begin to think about the amount of debt we're adding to our country and the future impact of that."

"Until we can begin to open up the economy, we can't spend enough money to solve the problem," he said, adding, "Let's weigh this very carefully because the future of our country in terms of the amount of debt that we're adding up is a matter of genuine concern."

Then on Wednesday, McConnell told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt: "Fortunately, what they wanted to extract the most, I refused to go along with, and the White House backed me up, and that was we’re not ready to just send a blank check down to states and local governments to spend anyway they choose to."

He added that "we need to have a full debate not only about if we do state and local, how will they spend it."

Following the Great Recession, state and local governments took years longer to recover than their federal counterparts, contributing to a sustained drag on the economy.

The White House has acknowledged the bind these governments are in. Speaking to reporters Monday, White House senior adviser Kevin Hassett said the funding boost was on the president's "radar" and "if you look at state budgets, they're in about as bad a state as you've ever seen because the economy more or less ground to a halt."

On Tuesday, Trump tweeted, "After I sign this Bill, we will begin discussions on the next Legislative Initiative with fiscal relief to State/Local Governments for lost revenues from COVID-19," among other packages.

Asked what she'd say to those who think such a massive price-tag is too much, Whaley pointed to the total percentage of the workforce that state and local governments employ. "You want to talk about a drag on the economy, have state and locals be out of business," she said.

Chase, of the National Association of Counties, said while there's a narrative that state and local governments — because of certain prominent budget crises — are fiscally irresponsible, "that's furthest from the truth."

"We have counties that have been very fiscally responsible," he said, "but when you lose this amount of revenue, you can never save enough money."

Linda Bilmes, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and a leading expert on public budgetary and financing issues, told NBC News that the nature of the crisis prevents states from raising new revenue in traditional ways.

"Can you increase property taxes, retail taxes, income taxes, special investments? Can you increase service fees? Well, no," she added. "Nobody's using services, toll roads. Can you expand the number of fees? Can you increase traffic violations? Well, nobody's driving."

These governments will need to instead lay off or furlough workers, reduce benefits, cancel projects, defer construction and maintenance, and more.

"But the problem is that by doing all of those kind of things and canceling a lot of those kind of capital projects, those are the things that create employment and activity in the community and in the economy," Bilmes said, adding, "It's certainly capable of derailing a recovery or creating a second wave of recession."

Already, governors, mayors and county executives are planning for substantial budget cuts. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, a Democrat, slashed roughly $235 million in planned spending. In Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, estimates suggest that billions in projected revenue over the next year will vanish. At the county-level, the National Association of Counties estimates close to $150 billion in lost revenue.

Matthew Chase, executive director of the National Association of Counties, said counties are watching as revenue from sales and gas taxes, court filing fees and mortgage transactions evaporate. The losses mean "you're going to see a cut in the staff at the exact wrong time, when their residents actually are going to need more services."

State and local governments employ more than 10 percent of the overall U.S. workforce, including police officers, firefighters and public-school teachers. State governments heavily subsidize public universities and finance significant construction projects, while local governments handle everything from trash collection to filling potholes.

Nan Whaley, the mayor of Dayton, Ohio, said her administration felt the impact of the outbreak on its budget "right away," and quickly furloughed nearly a quarter of the city's employees and have since instituted a hiring freeze. She's asked her departments to provide guidance on what an 18 percent spending cut would look like, which she said would affect police, fire and trash pickup, among other services.

"In 2009, in the Great Recession, most midsized cities in the middle of the country were decimated. We cut like 40 percent of our employees then," said Whaley, a Democrat. "So we are on bare bones as it is."

This crisis, Whaley believes, "will be even worse than the Great Recession — by a factor of at least two."

In Oklahoma City, Mayor David Holt, a Republican, said his city faces budget cuts of 3.3 percent for police and firefighters and 11.25 percent for all other departments for the upcoming fiscal year. But Holt says his city is buoyed by a more than $100 million reserve fund.

"We're always prepared for bad stuff to happen," he said. "Nevertheless ... these are probably some of the biggest cuts here in Oklahoma City that we've taken in the last two decades."

Federal intervention will be needed within a couple of months, Holt said.

The National Governors Association has called for $500 billion in funding to state governments to account for budget shortfalls, while counties and mayors have called for an additional $250 billion in emergency relief. On Monday, Sens. Bill Cassidy, R-La., and Bob Menendez, D-N.J., unveiled a legislative proposal for $500 billion in state and local funding.

"In this crazy and political environment where you can't get Democrats and Republicans to agree on anything," New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, said, "all the governors agree and have said to Washington, 'Make sure you fund the states in any next bill you pass.'"

In three Rust Belt states, Govs. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania and Tony Evers of Wisconsin, all Democrats, wrote to President Donald Trump last week asking him to work with Congress to get states and localities more funding.

"Without this leadership, the damage to our state economies will be exacerbated by the cuts we know we will be forced to make," they said.

The boost won't be coming in this current round of coronavirus aid, though Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., sounded optimistic it would be included in a future aid package.

In a letter to senators, Schumer said he was "disappointed" the funding was not part of the upcoming bill but added that "as a part of this agreement, we were able to secure a commitment from (Treasury) Secretary Mnuchin that he will support additional state and local relief in the next COVID-19 legislation, as well as a provision providing the flexibility to use all past and future relief dollars to offset lost revenues."

However, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., seemed to throw cold water on the possibility of additional massive relief bills, telling reporters Tuesday he thinks "it's also time to begin to think about the amount of debt we're adding to our country and the future impact of that."

"Until we can begin to open up the economy, we can't spend enough money to solve the problem," he said, adding, "Let's weigh this very carefully because the future of our country in terms of the amount of debt that we're adding up is a matter of genuine concern."

Then on Wednesday, McConnell told conservative radio host Hugh Hewitt: "Fortunately, what they wanted to extract the most, I refused to go along with, and the White House backed me up, and that was we’re not ready to just send a blank check down to states and local governments to spend anyway they choose to."

He added that "we need to have a full debate not only about if we do state and local, how will they spend it."

Following the Great Recession, state and local governments took years longer to recover than their federal counterparts, contributing to a sustained drag on the economy.

The White House has acknowledged the bind these governments are in. Speaking to reporters Monday, White House senior adviser Kevin Hassett said the funding boost was on the president's "radar" and "if you look at state budgets, they're in about as bad a state as you've ever seen because the economy more or less ground to a halt."

On Tuesday, Trump tweeted, "After I sign this Bill, we will begin discussions on the next Legislative Initiative with fiscal relief to State/Local Governments for lost revenues from COVID-19," among other packages.

Asked what she'd say to those who think such a massive price-tag is too much, Whaley pointed to the total percentage of the workforce that state and local governments employ. "You want to talk about a drag on the economy, have state and locals be out of business," she said.

Chase, of the National Association of Counties, said while there's a narrative that state and local governments — because of certain prominent budget crises — are fiscally irresponsible, "that's furthest from the truth."

"We have counties that have been very fiscally responsible," he said, "but when you lose this amount of revenue, you can never save enough money."

No comments:

Post a Comment