The Kamala Harris enigma: A daughter of immigrants, now running for the highest office in the land

Born to an Indian mother and Jamaican father, she’s been attorney general, senator, vice president and now, an unexpected presidential hopeful who might be able to stand in Trump’s way. She is defined by ambition, and has been underestimated countless times, says her biographer

Kamala Harris, at a 2021 White House event.

KEVIN MOHATT (REUTERS)

Washington / Los Angeles -

JUL 31, 2024 - 04:27 EDT

The first plot twist in the quintessentially Californian story of Kamala Harris — whose first name means “lotus flower” — took place in Montreal, far from the San Francisco Bay Area where the U.S. vice president was born and raised as the daughter of an Indian mother and Jamaican father. Her parents met through the circles of1970s (1960s) political activism and divorced soon after getting married. Harris’s mother Shyamala Gopalan had built a career as a reputable oncological researcher when she received a job offer from a Canadian university that she couldn’t refuse. “I was 12 years old, and the thought of moving away from sunny California in February, in the middle of the school year, to a French-speaking foreign city covered in 12 feet of snow was distressing,” writes Harris in her memoir.

Once she got over her distress, the young girl joined a dance group called Midnight Magic, in which she perfected a dance style that would turn the unexpected U.S. Democratic presidential candidate into the latest TikTok sensation. One day, when Wanda Kagan, her best friend in high school, told Harris that her stepfather had abused her, the future politician’s family, including Maya, her younger sister who today is a public policy expert, had her move in. Harris says that the experience convinced her to become a prosecutor, “to protect people like Wanda.”

“She more than fulfilled that goal,” says Dan Morain, a reporter who began following Harris’s career in 1994 and is the author of a superlative biography, Kamala’s Way (Simon & Schuster). “Kamala came back from Montreal, finished her studies and wound up working as a deputy district attorney in Alameda County, was the district attorney of San Francisco and attorney general of California. Then she made the leap to national politics as a senator.” Now she’s on the brink of becoming the first woman president in the history of the United States.

The first plot twist in the quintessentially Californian story of Kamala Harris — whose first name means “lotus flower” — took place in Montreal, far from the San Francisco Bay Area where the U.S. vice president was born and raised as the daughter of an Indian mother and Jamaican father. Her parents met through the circles of

Once she got over her distress, the young girl joined a dance group called Midnight Magic, in which she perfected a dance style that would turn the unexpected U.S. Democratic presidential candidate into the latest TikTok sensation. One day, when Wanda Kagan, her best friend in high school, told Harris that her stepfather had abused her, the future politician’s family, including Maya, her younger sister who today is a public policy expert, had her move in. Harris says that the experience convinced her to become a prosecutor, “to protect people like Wanda.”

“She more than fulfilled that goal,” says Dan Morain, a reporter who began following Harris’s career in 1994 and is the author of a superlative biography, Kamala’s Way (Simon & Schuster). “Kamala came back from Montreal, finished her studies and wound up working as a deputy district attorney in Alameda County, was the district attorney of San Francisco and attorney general of California. Then she made the leap to national politics as a senator.” Now she’s on the brink of becoming the first woman president in the history of the United States.

Harris, 59, does not include the story of her friend’s abuse in her memoir, The Truths We Hold: An American Journey (2019), a book that serves as a classic example of that supremely Washington D.C. literary genre blending autobiographical tales with a compendium of political reflections. She did, however, resurrect it for the 2020 Democratic primaries. Her campaign in that round was a failure, but she did well enough for Joe Biden to end up choosing her as his vice-presidential candidate. In 2021, she became the first woman and the first person of mixed Black and South Asian American heritage to become VP.

Curiously, there is only one passing reference to Biden in the pages of The Truths We Hold, which takes place as Harris is sworn in as senator in his presence, just one month before he would step down as vice president. The period was a turning point in Biden’s long political career, which essentially came to an end a week ago. Through social media, Biden announced that he was dropping out of his re-election campaign, and 27 minutes later, he endorsed his second-in-command for the task of defeating Republican Donald Trump.

Harris received the earth-shaking news not long before the rest of the world. She was made aware of the historic occasion at her official residence, a Victorian-style home located on the grounds of the U.S. Naval Observatory, northeast of Washington D.C. She had no time to change out of her workout sweats and hoodie from Howard University, her alma mater, before starting to call members of Congress, senators and key members of her political party. She had to make sure she had enough votes among August’s Democratic National Convention delegates, a task she was able to complete in just over 24 hours. Her collaborators in this urgent moment that began on a sleepy Sunday calculate that the vice president made around 100 phone calls in 10 hours. “That gives you an idea of what is perhaps her defining characteristic: ambition,” says Morain. “It’s not necessarily a bad thing: all politicians have it. In her case, the goal was to rise as high as possible.”

Kamala, her younger sister Maya and their mother Shyamala Gopalan in 1970.

OFICINA DE CAMPAÑA DE KAMALA HARRIS (AP)

Harris was making it clear that she does not intend to let this opportunity pass her by. Prior to Sunday, she had one of the lowest popularity ratings ever for one of the hardest jobs in U.S. politics, to which she arrived accompanied by overly high expectations that were promptly deflated. This week, she emerged as a candidate capable of uniting the party’s heavyweights, from Nancy Pelosi to the Obamas, who finally endorsed her on Friday; of provoking enthusiasm among the Democratic base, especially among its women; of making Trump nervous; of demonstrating that there is still hope for certain swing states that Biden had given up for lost; of exciting young people and people of color to vote and of bringing in a flood of campaign donations, to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

She has also obliterated all expectations when it comes to the cultural front. Beyoncé allowed the Harris campaign to use one of her songs and British singer Charlie XCX donated a color, a green somewhere between lime and fluoride, and a nickname, “brat”. The artist and her fans use the word to define a certain unbothered, daring femininity. Meanwhile, a legion of internet users is working selflessly to get Harris to the White House via memes, with the now famous and somewhat surreal “coconut tree” video serving as standard-bearer. In it, Harris is seen at an event at the White House remembering her mother, whom she calls her greatest influence in her memoir. “My mother used to say to us, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with you young people. You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?’ You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you,” she says, before launching into one of her infectious laughs.

“Before [Biden dropped out] we were rowing with both oars,” sums up Juan Verde, a strategist who has worked on all the Democratic presidential campaigns since Bill Clinton, is a member of Biden’s cabinet, and who has been seen this week with Harris getting her campaign off the ground. “Now we’re trying to trim sails in storm. I’m noticing hope that reminds me in a certain way of Barack Obama’s campaign. The challenge will be to maintain that enthusiasm and for voters to get to know the real Kamala, a woman whose own experience as an immigrant makes her very empathetic, but who is also very tough.”

To decode the Harris enigma, her biographer recommends not forgetting that this is a person who exercises “enormous control over her public persona.” For now, she is spotlighting her past as a lawyer, in the hopes of presenting her race against Trump as that of a prosecutor and a convicted felon, a man who is guilty of 34 felonies in the Stormy Daniels case and who has at least two more criminal trials pending.

This strategy has made Trump and his campaign nervous. They clearly had a better handle on how to face off against an 81-year-old man like Biden, as opposed to a 59-year-old woman like Harris. Attacks on Harris’s candidacy rolled out on two contradictory fronts this week. In a thought experiment in the style of Schrödinger’s cat, she has been accused of being both too tough and too soft on crime. [In fact, Harris titled her first book in 2009 Smart on Crime.]

The first of these two critiques comes from the leftist factions of California’s prison reform movement, who provided reminders of how when she was district attorney, she was credited with refusing to send prisoners to death row (capital punishment has not been applied in the state since 2006), prosecuting sexual predators and bravely standing up to powerful banks during the Great Recession, which was still raging at the time. However, they lament her record of wrongful convictions, incarceration of Black men and of sending people to prison on charges of marijuana possession.

Proponents of Harris being too soft on crime have tried to present her as being lax with delinquents and too progressive to operate outside of California. Trump, a man of many talents when it comes to personal insults, seems to have lacked good ideas over the past week, limiting himself to insinuating that her rise is the product of reverse discrimination and repeatedly referring as to Harris being “a San Francisco liberal” and “the most extreme radical liberal vice-president in American history.”

San Francisco, a lawless town?

“I fear that Republicans don’t understand anything that happens west of the Rockies. And that it’s easy for them to represent San Francisco as a lawless town,” says Oakland writer Ishmael Reed by telephone. A legend of African American letters, Reed belongs to a generation of Black thinkers who influenced Harris when she was just a little girl who accompanied her mother on trips to The Rainbow Sign cultural center, where the future vice president took in talks by Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman in U.S. Congress, novelist Alice Walker and poet Maya Angelou.

Reed met Harris soon after she won her election as California attorney general. “It was a fundraising event at the San Francisco Jazz Center,” remembers the Mumbo Jumbo author. “I asked her, ‘When are you running for governor?’ To which she responded, ‘All in due time, Ishmael.’”

Harris was making it clear that she does not intend to let this opportunity pass her by. Prior to Sunday, she had one of the lowest popularity ratings ever for one of the hardest jobs in U.S. politics, to which she arrived accompanied by overly high expectations that were promptly deflated. This week, she emerged as a candidate capable of uniting the party’s heavyweights, from Nancy Pelosi to the Obamas, who finally endorsed her on Friday; of provoking enthusiasm among the Democratic base, especially among its women; of making Trump nervous; of demonstrating that there is still hope for certain swing states that Biden had given up for lost; of exciting young people and people of color to vote and of bringing in a flood of campaign donations, to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

She has also obliterated all expectations when it comes to the cultural front. Beyoncé allowed the Harris campaign to use one of her songs and British singer Charlie XCX donated a color, a green somewhere between lime and fluoride, and a nickname, “brat”. The artist and her fans use the word to define a certain unbothered, daring femininity. Meanwhile, a legion of internet users is working selflessly to get Harris to the White House via memes, with the now famous and somewhat surreal “coconut tree” video serving as standard-bearer. In it, Harris is seen at an event at the White House remembering her mother, whom she calls her greatest influence in her memoir. “My mother used to say to us, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with you young people. You think you just fell out of a coconut tree?’ You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you,” she says, before launching into one of her infectious laughs.

“Before [Biden dropped out] we were rowing with both oars,” sums up Juan Verde, a strategist who has worked on all the Democratic presidential campaigns since Bill Clinton, is a member of Biden’s cabinet, and who has been seen this week with Harris getting her campaign off the ground. “Now we’re trying to trim sails in storm. I’m noticing hope that reminds me in a certain way of Barack Obama’s campaign. The challenge will be to maintain that enthusiasm and for voters to get to know the real Kamala, a woman whose own experience as an immigrant makes her very empathetic, but who is also very tough.”

To decode the Harris enigma, her biographer recommends not forgetting that this is a person who exercises “enormous control over her public persona.” For now, she is spotlighting her past as a lawyer, in the hopes of presenting her race against Trump as that of a prosecutor and a convicted felon, a man who is guilty of 34 felonies in the Stormy Daniels case and who has at least two more criminal trials pending.

This strategy has made Trump and his campaign nervous. They clearly had a better handle on how to face off against an 81-year-old man like Biden, as opposed to a 59-year-old woman like Harris. Attacks on Harris’s candidacy rolled out on two contradictory fronts this week. In a thought experiment in the style of Schrödinger’s cat, she has been accused of being both too tough and too soft on crime. [In fact, Harris titled her first book in 2009 Smart on Crime.]

The first of these two critiques comes from the leftist factions of California’s prison reform movement, who provided reminders of how when she was district attorney, she was credited with refusing to send prisoners to death row (capital punishment has not been applied in the state since 2006), prosecuting sexual predators and bravely standing up to powerful banks during the Great Recession, which was still raging at the time. However, they lament her record of wrongful convictions, incarceration of Black men and of sending people to prison on charges of marijuana possession.

Proponents of Harris being too soft on crime have tried to present her as being lax with delinquents and too progressive to operate outside of California. Trump, a man of many talents when it comes to personal insults, seems to have lacked good ideas over the past week, limiting himself to insinuating that her rise is the product of reverse discrimination and repeatedly referring as to Harris being “a San Francisco liberal” and “the most extreme radical liberal vice-president in American history.”

San Francisco, a lawless town?

“I fear that Republicans don’t understand anything that happens west of the Rockies. And that it’s easy for them to represent San Francisco as a lawless town,” says Oakland writer Ishmael Reed by telephone. A legend of African American letters, Reed belongs to a generation of Black thinkers who influenced Harris when she was just a little girl who accompanied her mother on trips to The Rainbow Sign cultural center, where the future vice president took in talks by Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman in U.S. Congress, novelist Alice Walker and poet Maya Angelou.

Reed met Harris soon after she won her election as California attorney general. “It was a fundraising event at the San Francisco Jazz Center,” remembers the Mumbo Jumbo author. “I asked her, ‘When are you running for governor?’ To which she responded, ‘All in due time, Ishmael.’”

Harris in her graduation photo from Howard University in 1986.

FACEBOOK

The truth is that it’s often said that the initials of “attorney general” (AG) actually stand for “aspiring governor.” Harris skipped that step when, in 2016, she ran for the Senate and won handily. Her biographer credits her leap from practicing law to politics to two factors: her years at Howard, Washington D.C.’s historically Black university that is often referred to as the Mecca, a period during which she became involved in the struggle against apartheid, and her 1990s relationship with California Speaker of the House Willie Brown, whom Harris does not mention in her memoir. “She learned a lot from watching how he approached his campaign for mayor of San Francisco [a post he held from 1996 to 2004],” says Morain, who places the vice president among “a glorious generation of Bay Area politicians,” including former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Senators Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, the latter whose Washington seat Harris would eventually assume.

“I’ve stopped counting the number of times that she has been underestimated in an electoral campaign,” says her biographer. “She thrives when they look down on her. That worked very well for her when she ran for attorney general, and it could work for her now.” Morain says that in that first statewide election, Harris’s Republican rivals fell over themselves to defeat the 30-something, who broke the mold of the position’s traditional incumbent, a gray-haired white man. They wanted to put an end to a career that was clearly on the rise. “They didn’t succeed, and they still regret it,” he says.

Angélica Salas, executive director of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), says that Harris’s election to state attorney general was a deciding factor that led to California becoming a sanctuary state for undocumented individuals. “She ordered the police not to hold immigrants until ICE agents arrived, she supported our people in bank foreclosures and workers who were facing workplace exploitation,” she says. Salas also remembers that when Harris was running for senator, she went to the CHIRLA offices seeking their campaign endorsement. “There was another candidate, Loretta Sanchez, who was more centrist, she was the Latina, and came and told us, ‘Support me, I’m the one who speaks Spanish.’ Kamala, on the other hand, came in very prepared, we really felt like she needed us. We were criticized because of it, but we supported her,” says Salas.

Los Angeles life

Harris won her Senate election the same day that Trump defeated Hillary Clinton, and the memory of that bittersweet victory is what opens her memoir, which is dedicated to her husband Doug Emhoff for being, “patient, loving, understanding and calm.” They got married in 2014. At 59 years old, Emhoff is an entertainment industry lawyer and has two children from a previous marriage. Harris has played an active role in their upbringing. The couple splits their time between Los Angeles and Washington D.C., where it is not unusual to see them grocery shopping, buying jazz records (an interest Harris inherited from her father) or picking up an anchovy pizza to go. On the West Coast, they live in a $5 million home in Brentwood, an exclusive neighborhood on the Westside of Los Angeles. Among their neighbors, who must deal with street closures when the couple arrives to spend the weekend, are Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jim Carrey and rapper Dr. Dre.

The truth is that it’s often said that the initials of “attorney general” (AG) actually stand for “aspiring governor.” Harris skipped that step when, in 2016, she ran for the Senate and won handily. Her biographer credits her leap from practicing law to politics to two factors: her years at Howard, Washington D.C.’s historically Black university that is often referred to as the Mecca, a period during which she became involved in the struggle against apartheid, and her 1990s relationship with California Speaker of the House Willie Brown, whom Harris does not mention in her memoir. “She learned a lot from watching how he approached his campaign for mayor of San Francisco [a post he held from 1996 to 2004],” says Morain, who places the vice president among “a glorious generation of Bay Area politicians,” including former Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Senators Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, the latter whose Washington seat Harris would eventually assume.

“I’ve stopped counting the number of times that she has been underestimated in an electoral campaign,” says her biographer. “She thrives when they look down on her. That worked very well for her when she ran for attorney general, and it could work for her now.” Morain says that in that first statewide election, Harris’s Republican rivals fell over themselves to defeat the 30-something, who broke the mold of the position’s traditional incumbent, a gray-haired white man. They wanted to put an end to a career that was clearly on the rise. “They didn’t succeed, and they still regret it,” he says.

Angélica Salas, executive director of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), says that Harris’s election to state attorney general was a deciding factor that led to California becoming a sanctuary state for undocumented individuals. “She ordered the police not to hold immigrants until ICE agents arrived, she supported our people in bank foreclosures and workers who were facing workplace exploitation,” she says. Salas also remembers that when Harris was running for senator, she went to the CHIRLA offices seeking their campaign endorsement. “There was another candidate, Loretta Sanchez, who was more centrist, she was the Latina, and came and told us, ‘Support me, I’m the one who speaks Spanish.’ Kamala, on the other hand, came in very prepared, we really felt like she needed us. We were criticized because of it, but we supported her,” says Salas.

Los Angeles life

Harris won her Senate election the same day that Trump defeated Hillary Clinton, and the memory of that bittersweet victory is what opens her memoir, which is dedicated to her husband Doug Emhoff for being, “patient, loving, understanding and calm.” They got married in 2014. At 59 years old, Emhoff is an entertainment industry lawyer and has two children from a previous marriage. Harris has played an active role in their upbringing. The couple splits their time between Los Angeles and Washington D.C., where it is not unusual to see them grocery shopping, buying jazz records (an interest Harris inherited from her father) or picking up an anchovy pizza to go. On the West Coast, they live in a $5 million home in Brentwood, an exclusive neighborhood on the Westside of Los Angeles. Among their neighbors, who must deal with street closures when the couple arrives to spend the weekend, are Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gwyneth Paltrow, Jim Carrey and rapper Dr. Dre.

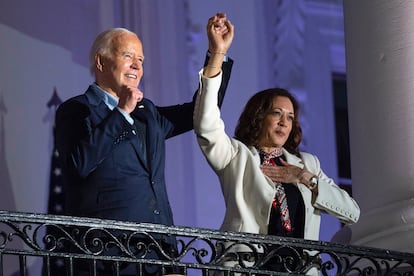

Kamala Harris and Joe Biden on July 4 at the White House during Independence Day celebrations.EVAN VUCCI (AP)

Her swearing-in as senator took place in 2018, during the confirmation hearings for conservative Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, whom a woman accused of trying to rape her when they were both high school students. Harris gave a lesson in calm, intelligent on-camera questioning during his hearing. She wanted to know if Kavanaugh would be on a mission in the Supreme Court to overturn 1973′s Roe v. Wade ruling, which established federal protections for abortion. “Can you think of any laws that give government the power to make decisions about the male body?” asked the senator. The judge said, “I’m not thinking of any right now, senator.” Four years later, Kavanaugh, one of three judges who were nominated by Trump, voted with the high court’s conservative majority to overturn Roe, setting back the clock by 50 years for U.S. women.

The defense of reproductive rights would come to be one the vice president’s key issues. She feels comfortable in that territory, which will be crucial when it comes to the November election. “It’s an issue of maximum importance for voters,” writes Alexis McGill Johnson, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Action Fund, the non-profit’s political arm, in an email. “I’ve had the privilege of working and campaigning with her and can say that she is one of the strongest voices when it comes to the defense of our rights. She has spent a lot of time and energy on speaking with doctors, patients, activists and advocates, which leads me to believe that she will take the conversation around abortion rights to unprecedented heights in the presidential campaign.”

Angela Romero, minority leader of the House of Representatives in Utah, one of the states whose Democratic Party rushed to support Harris’ candidacy, recalls meeting with Harris and other women lawmakers shortly after the Supreme Court ruling. “That’s when we saw that she knew the issue in depth,” says Romero, who was one of Harris’s guests at the debate that pitted her against Trump’s previous vice-presidential candidate, Mike Pence.

That night constituted a missed opportunity for Harris to abandon the low profile she’d maintained throughout the 2020 campaign. This time, she didn’t measure up to expectations — and you could say the same thing about her years as vice president.

The way she handled the first task given to her by the Biden administration can only be classified as disappointing. He asked her to lead diplomatic relations with the so-called Northern Triangle of Central America: Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, and to address the “root causes” of migration from the three countries. On her first international trip in office, she sent a two-word directive to the migrants in Guatemala, “don’t come,” for which she was showered in criticism. As the migration crisis worsened, she said in a television interview that she did not understand migrants’ urgency in getting to the U.S.-Mexico border. Republicans are now trying to pin a title on her that she never held: “border czar.” Romero, who is chairperson of the National Hispanic Caucus of State Legislators, excuses her, saying that Biden’s charge was “not an easy task.” “Without congressional action, which is paralyzed, little can be done. It’s a broken system,” says Romero.

Harris has also been accused of not being in tune with the president, of carrying out work too minor even in a position for which the trick is not to stand out too much, and also of being a terrible boss (dozens of staff members have left her office during the administration.) “It was hard for her to find a place in Washington,” says Verde.

Over the last two years her image has improved, thanks to her role in the defense of abortion, and particularly as doubts surged as to the physical and cognitive capabilities of Biden leading up to his disastrous June 27 debate in Atlanta against Trump. It was a pitiful spectacle fraught with lapses and unfinished sentences that lifted the Democrats’ ban on calling for his resignation.

Two days after that debate, Harris was deployed to an evening with donors at the Los Angeles home of filmmaker Rob Reiner. She trotted out a discourse that she perfected after the regrettable showdown, a difficult equilibrium between appearing loyal to her boss in their efforts to seek re-election and showing herself as ready to replace him if necessary. “During those moments of uncertainty, some of us, myself included, kept organizing fundraisers for Biden,” James Costos, a Hollywood executive and former U.S. ambassador to Spain, told EL PAÍS this week. “Later, when the president endorsed her, donors acted quickly and decisively.”

Costos was there that night with his husband, interior designer Michael Smith, among the hosts of the party that was organized to commemorate the 10th anniversary of marriage rights in the United States. Among the guests were Kris Perry and Sandy Stier, a lesbian couple who launched a crusade against California’s Prop 8, which banned same-sex marriages in 2008 and who had the full support of Harris, who was then state attorney general. Their case arrived at the Supreme Court, who declared the law unconstitutional.

Perhaps the most-repeated phrase in Morain’s biography is, “no one could have imagined.” On that night in June, no one could have imagined that one month later, Harris would have been capable of shaking up her own life and the presidential campaign in this manner. Perhaps because it was never easy to imagine that the daughter of a young woman from New Delhi, who arrived at the University of California Berkeley aged 19 and met Donald Harris, a brilliant Jamaican student and future Stanford professor, would, after just one generation, wind up running for the presidency. That daughter writes in her memoir that one of her favorite sayings of her mother, who died in 2009, was: “Don’t let anyone tell you who you are. Tell them yourself.” “That’s what I did,” Harris adds.

She’s now faced with the need to once again define herself. Harris has only 100 days to tell her fellow Americans on both sides of the cultural divide that splits the country who she is and why she should be the first woman president in the history of the United States.

Her swearing-in as senator took place in 2018, during the confirmation hearings for conservative Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, whom a woman accused of trying to rape her when they were both high school students. Harris gave a lesson in calm, intelligent on-camera questioning during his hearing. She wanted to know if Kavanaugh would be on a mission in the Supreme Court to overturn 1973′s Roe v. Wade ruling, which established federal protections for abortion. “Can you think of any laws that give government the power to make decisions about the male body?” asked the senator. The judge said, “I’m not thinking of any right now, senator.” Four years later, Kavanaugh, one of three judges who were nominated by Trump, voted with the high court’s conservative majority to overturn Roe, setting back the clock by 50 years for U.S. women.

The defense of reproductive rights would come to be one the vice president’s key issues. She feels comfortable in that territory, which will be crucial when it comes to the November election. “It’s an issue of maximum importance for voters,” writes Alexis McGill Johnson, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood Action Fund, the non-profit’s political arm, in an email. “I’ve had the privilege of working and campaigning with her and can say that she is one of the strongest voices when it comes to the defense of our rights. She has spent a lot of time and energy on speaking with doctors, patients, activists and advocates, which leads me to believe that she will take the conversation around abortion rights to unprecedented heights in the presidential campaign.”

Angela Romero, minority leader of the House of Representatives in Utah, one of the states whose Democratic Party rushed to support Harris’ candidacy, recalls meeting with Harris and other women lawmakers shortly after the Supreme Court ruling. “That’s when we saw that she knew the issue in depth,” says Romero, who was one of Harris’s guests at the debate that pitted her against Trump’s previous vice-presidential candidate, Mike Pence.

That night constituted a missed opportunity for Harris to abandon the low profile she’d maintained throughout the 2020 campaign. This time, she didn’t measure up to expectations — and you could say the same thing about her years as vice president.

The way she handled the first task given to her by the Biden administration can only be classified as disappointing. He asked her to lead diplomatic relations with the so-called Northern Triangle of Central America: Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, and to address the “root causes” of migration from the three countries. On her first international trip in office, she sent a two-word directive to the migrants in Guatemala, “don’t come,” for which she was showered in criticism. As the migration crisis worsened, she said in a television interview that she did not understand migrants’ urgency in getting to the U.S.-Mexico border. Republicans are now trying to pin a title on her that she never held: “border czar.” Romero, who is chairperson of the National Hispanic Caucus of State Legislators, excuses her, saying that Biden’s charge was “not an easy task.” “Without congressional action, which is paralyzed, little can be done. It’s a broken system,” says Romero.

Harris has also been accused of not being in tune with the president, of carrying out work too minor even in a position for which the trick is not to stand out too much, and also of being a terrible boss (dozens of staff members have left her office during the administration.) “It was hard for her to find a place in Washington,” says Verde.

Over the last two years her image has improved, thanks to her role in the defense of abortion, and particularly as doubts surged as to the physical and cognitive capabilities of Biden leading up to his disastrous June 27 debate in Atlanta against Trump. It was a pitiful spectacle fraught with lapses and unfinished sentences that lifted the Democrats’ ban on calling for his resignation.

Two days after that debate, Harris was deployed to an evening with donors at the Los Angeles home of filmmaker Rob Reiner. She trotted out a discourse that she perfected after the regrettable showdown, a difficult equilibrium between appearing loyal to her boss in their efforts to seek re-election and showing herself as ready to replace him if necessary. “During those moments of uncertainty, some of us, myself included, kept organizing fundraisers for Biden,” James Costos, a Hollywood executive and former U.S. ambassador to Spain, told EL PAÍS this week. “Later, when the president endorsed her, donors acted quickly and decisively.”

Costos was there that night with his husband, interior designer Michael Smith, among the hosts of the party that was organized to commemorate the 10th anniversary of marriage rights in the United States. Among the guests were Kris Perry and Sandy Stier, a lesbian couple who launched a crusade against California’s Prop 8, which banned same-sex marriages in 2008 and who had the full support of Harris, who was then state attorney general. Their case arrived at the Supreme Court, who declared the law unconstitutional.

Perhaps the most-repeated phrase in Morain’s biography is, “no one could have imagined.” On that night in June, no one could have imagined that one month later, Harris would have been capable of shaking up her own life and the presidential campaign in this manner. Perhaps because it was never easy to imagine that the daughter of a young woman from New Delhi, who arrived at the University of California Berkeley aged 19 and met Donald Harris, a brilliant Jamaican student and future Stanford professor, would, after just one generation, wind up running for the presidency. That daughter writes in her memoir that one of her favorite sayings of her mother, who died in 2009, was: “Don’t let anyone tell you who you are. Tell them yourself.” “That’s what I did,” Harris adds.

She’s now faced with the need to once again define herself. Harris has only 100 days to tell her fellow Americans on both sides of the cultural divide that splits the country who she is and why she should be the first woman president in the history of the United States.

P.S. Bolds and Highlights added by blogger.

No comments:

Post a Comment